Ethereum

Unlike blockchains such as Bitcoin, which essentially allow Bitcoin cryptocurrency transactions to be sent, Ethereum also has something quite extraordinary: decentralized code execution.

Yes, decentralized. This means that we can write a program, code that is, and have it run not on one server, but on thousands of servers, or nodes. And the output of our program is also recorded in a decentralized way. I don’t know about you, but I think it’s incredible, and it really made me want to dig a little deeper into the subject.

So Ethereum is just another blockchain. There’s no shortage of blockchains today, but to date, Ethereum is the best-known and most widely used, at least in terms of blockchains that allow you to execute code. It does have its drawbacks, which other blockchains have addressed (albeit often to the detriment of other aspects), but that’s not really the point.

Let’s take a look at how Ethereum works, covering the notions of EOA accounts, contracts, states and transactions.

Ethereum 101

We discussed how blockchains work in general in the article Blockchain 101. Ethereum operates in a similar way, with the consensus mechanism being the Proof of Stake. Ethereum’s own cryptocurrency is Ether (or ETH). Like Bitcoin and all other blockchains, Ethers can be sent to other users via transactions. Each user has his own address.

What Ethereum brings is that, in addition to regular users who send transactions, it is possible to create small programs, smart contracts, which also live on the blockchain. They all have addresses, just like users, but they also have code, stored on the blockchain.

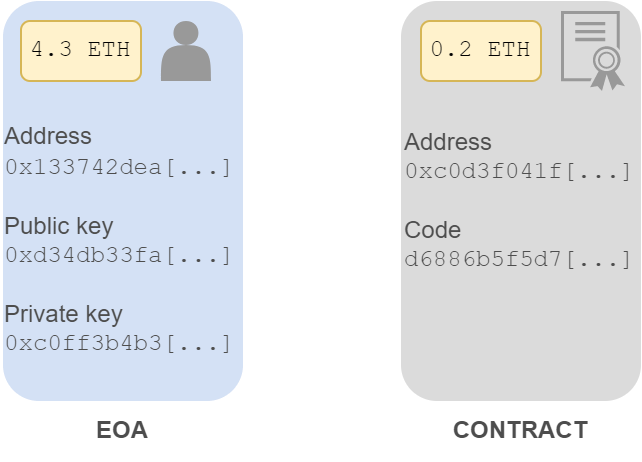

To distinguish these two types of accounts, we call classic human users EOA (Externally Owned Accounts), which we distinguish from contract accounts, which we’ll simply refer to as contracts.

EOA vs Contrats

Human-created accounts, or EOAs, are accounts with an address, a public key and a private key. They can initiate transactions by signing them, send Ethers and receive them. These transactions can be sent to other EOAs, allowing Ethers to be sent, but also to contracts.

Contracts also have an address, but no private key. They cannot initiate transactions. They can only react to transactions initiated by EOAs, or to messages sent by other contracts. Indeed, once called by an EOA, a contract can send messages to other contracts. The notion of message is discussed at the end of this article.

Data organization

Before we dive into why and how a contract account can execute code within the Ethereum ecosystem, let’s zoom in on the various data managed and used by Ethereum. Indeed, in this ecosystem, a global state of addresses must be kept up to date (with account balances, for example), the list of transactions must be stored and verifiable, the messages emitted in the various transactions must be accessible, and the permanent storage of each smart contract must, by definition, also be stored somewhere.

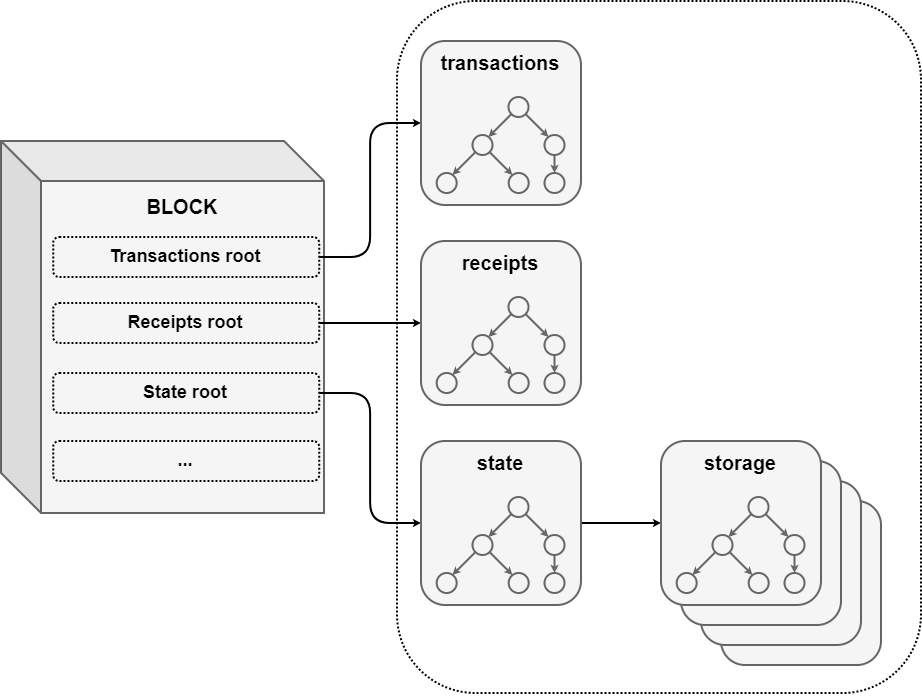

All this data is not stored in the blocks of the blockchain. Surprising as it may seem (at least to me at first sight), this information is stored in databases, outside the blocks, in the form of trees that follow a specific format: these are Merkle Patricia Tries, which enable a list of keys/values to be stored in an optimized way.

There’s no typo, it’s

Trie, notTree, in reference to the word Retrieve. We’ll probably see the Merkle Patricia Tries in detail in a dedicated article.

These data are therefore stored in the following trees:

- State trie, or world state, which itself contains links to storage tries. Transactions tries

- Receipt tries**

In blocks, only the hash of the root of each of these trees is stored.

It’s up to each client to know how to store the contents of the trees and manage queries based on the root node hash (not all clients use the same database solutions, by the way).

This enables lightweight devices (mobile, IoT) to synchronize quickly and easily with the blockchain without having to download huge volumes of data, so that they only know the root nodes hashes for each block. With this information, they can query full nodes, i.e. nodes that have stored the blockchain, and also all the data in the databases, to send them the few pieces of information they need to validate any given data.

Note that even an Ethereum full node only requires around 1TB of disk space. It’s accessible to everyone, which is why so many people participate in the decentralized network. There are also archive nodes. Unlike full nodes, which only synchronize with the last 128 blocks, archive nodes store the entire blockchain. For more information, please read this article.

Let’s see what these different data trees correspond to.

World State

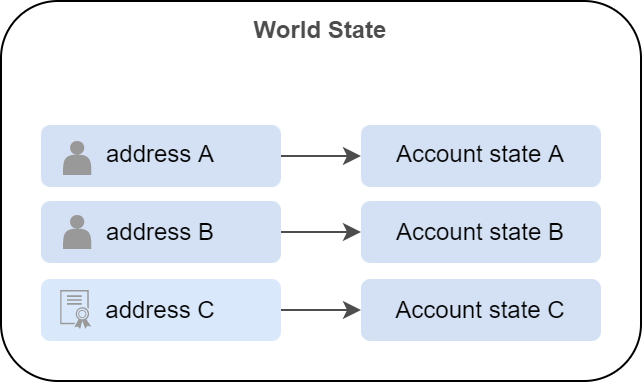

Let’s start with the State Trie, or World State. We can point out that, while we were comparing a blockchain to a decentralized database, Ethereum is more complex and comprehensive than that. Instead, we could describe Ethereum as a decentralized state machine.

So, the general state of Ethereum is called World State. In this world state, there are all active user addresses (i.e. addresses present in at least one transaction), and each address has an associated account state.

Account State

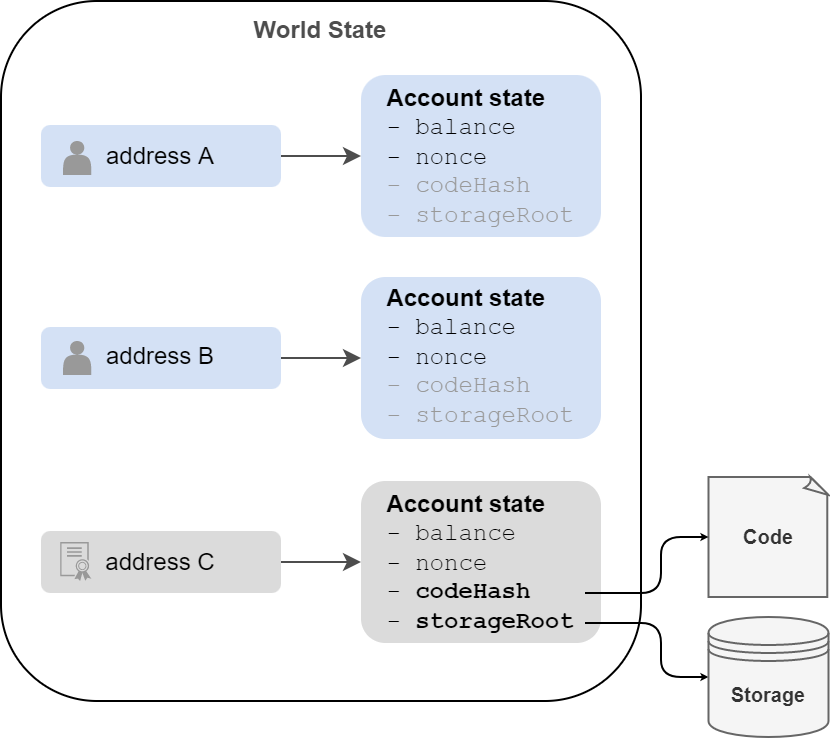

The status of each account is therefore recorded in the world state containing the following 4 fields:

balance: the account’s Ether balancenonce: A number that increments with each transaction for an EOA, and with each contract creation for a contract.codeHash: A hash that can be used to retrieve the smart contract’s code (the hash of an empty character string for an EOA).storageRoot: The root node hash of the Merkle Patricia Trie of account storage, or storage trie. It is used to retrieve the state of the contract, such as the value of permanently stored variables. This field is empty for an EOA account.

Each time a block on the blockchain is validated, all the transactions make changes to the world state, resulting in a new state.

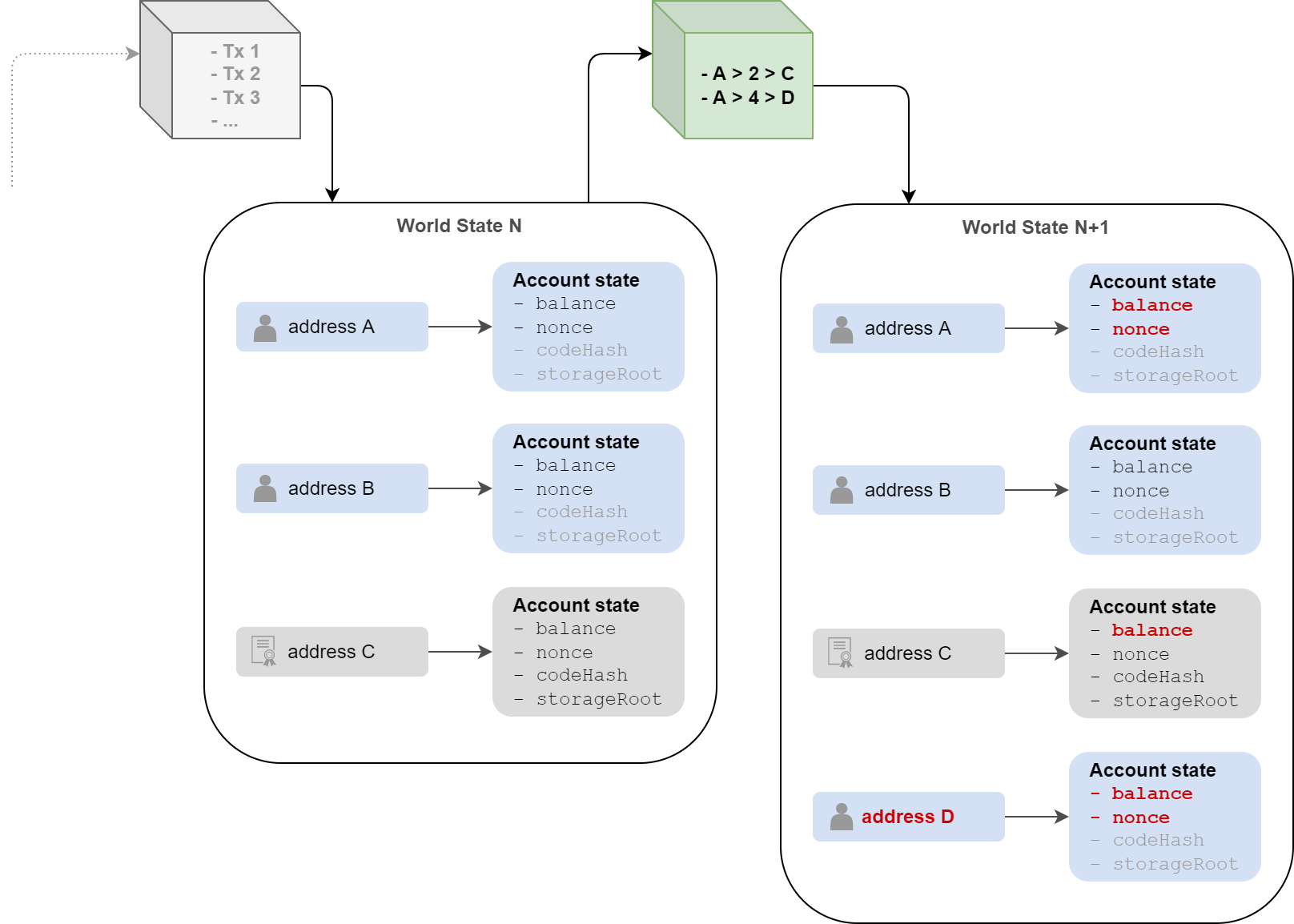

In the following diagram, a block sends two transactions:

- Address A sends 2 coins to address C. The balances (

balance) of A and C will be updated, as willnonceof A (which increments with each transaction). - Address A sends 4 coins to address D. The balance of A will be updated, and address D, which does not yet exist in the world state, will be added, with a balance of

2, and annonceequal to0.

The fields in red are therefore those that are modified following the execution of the block’s transactions, leading to a new N+1 state.

Transactions

We now have a more precise overview of the account types that exist, and how they are stored within Ethereum. We’ve explained that blocks contain transactions which modify the state of the involved accounts, and therefore the general state, or world state. These transactions are actually recorded in a database, the Transactions Trie, in an orderly fashion.

A transaction contains several elements:

nonce: Thenonceis specific to each account (stored for each address in the world state, if you’ve been following along), and is incremented for each new transaction.gasPriceandgasLimit: Allow the user to define transaction feesto: The destination address of the transaction- value`: The number of sent Eth

- v,r,s`: The user’s signature

data: Allows you to send data to another account, or to create a contract

If you’re an observer, you’ll notice that a transaction must be signed. However, the only type of account that has a private key is the EOA. Contracts don’t have private keys. Therefore, they cannot initiate a transaction.

There are actually two types of transaction in Ethereum, those that allow you to send a message to another account, and those that allow you to create a contract.

Sending a message

In a transaction, account A sends a message to account B. The to destination address is that of account B, and the value and data fields can be used.

Sending Ether

To send Ether to the destination address, the desired amount will be set in value. When an account sends Ether to another account, only the value field is filled in. The destination account may be an EOA or a contract.

If the destination is a contract, the contract must have been designed to receive Ethers.

Sending data

The data field is mainly used to execute the code of a smart contract, when the transaction is intended for it. It’s also possible to send data to an EOA, and the recipient will process it as it sees fit.

When calling a contract function, the data field must be formatted as follows:

data: <Sélecteur de la fonction> <arguments>

The function’s selector is computed by hashing the function’s signature, keeping only the first 4 bytes.

For example, let’s imagine the following function:

function getItemValue(string calldata _itemName, uint256 _itemId) public returns(uint256 value) {

// Function code

}

Function’s signature is:

getItemValue(string,uint256)

And it’s selector is:

bytes4(keccak256("getItemValue(string,uint256)"));

// Output:

0xc2e58fec

So data will be something like:

data: 0xc2e58fec<arguments>

We’ll see how the arguments are structured in a later article, but here’s an example for the getItemValue("pixis", 8) call:

0xc2e58fec # function selector

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000040 # pointer to string "pixis"

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000008 # 8

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000005 # string length

7069786973000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 # string "pixis"

This type of message can therefore be sent from an EOA account transaction to a smart contract.

Note that it is also possible for a contract to call another contract’s function by sending the same message format. Everything will happen in the same transaction, since a contract cannot sign a new transaction. This type of call between contracts is a message call, a specific instruction of the Ethereum virtual machine. Only the message is sent, the destination contract is executed, and the result of this call is returned to the calling contract. We’ll look at these calls in more detail in future articles.

Contract creation

The second type of transaction enables an EOA account to create a new contract. To do this, the transaction is sent to the null address 0x00000..., and the data field is used.

This data field is divided into two parts:

- The initialization bytecode, which is used to deploy the contract. It contains the contract constructor code and its arguments (if there is a constructor), as well as storage modifications if variables are declared. This code ends by returning the memory address of the *runtime bytecode and its size.

- The runtime bytecode is the contract code, which includes all functions code.

Once this transaction has been processed, a new contract account is created. Its address is derived from the contract creator’s address and his nonce. In this way, each time a new contract is created by the same user, a different address is generated.

As we saw earlier, a new entry in the world state will be created for this address. The nonce will be 0, the contract balance will depend on the value field of the transaction that created it (0 by default), but the most important fields are :

codeHash: used to locate the account’s runtime bytecode, i.e. all the smart contract’s logic.storageRoot: As a contract is always associated with a permanent storage, the account storage, this value is used to find this storage in order to read and modify all the variables used in the smart contract.

Receipts

The last Trie we haven’t talked about is the Receipts Trie. It is used to store information that is not required for the smart contracts to run properly, but which can be used by third-party applications, such as front-ends or clients.

This includes, for example, the status of the transaction (whether it failed or not), or the amount of gas used.

Furthermore, when a smart contract is executed, it can issue events.

contract MyContract {

// "Transfer" event declaration

Event Transfer(address to, uint value, uint tokenId);

function transferTokens(address _to, uint _value, uint _tokenId) external {

// Function code

// "Transfer" event emitted

emit Transfer(_to, _value, _tokenId);

}

}

In this example, the Transfer event is emitted at the end of the transferToken function. This event will be added to the Receipts Trie.

Conclusion

These various elements give us a better understanding of how Ethereum works, what defines a smart contract, how a user can create a smart contract and how he can interact with it. This article, together with Blockchain 101, lays the foundations for explaining how Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) works. But that’s for the next article!