Sensitive Data in smart contracts

Do you remember the different storage spaces to which the EVM has access? The one comparable to a computer hard disk is the account storage. This is the memory area in which the state of the contract is recorded. But you’ll also remember that the Ethereum blockchain is a decentralised state machine that can be read by anyone. Do you see where I’m going with this? All the data recorded by a smart contract can be read by anyone. If any sensitive data is recorded by a smart contract, we will be able to read it.

Memory reminder

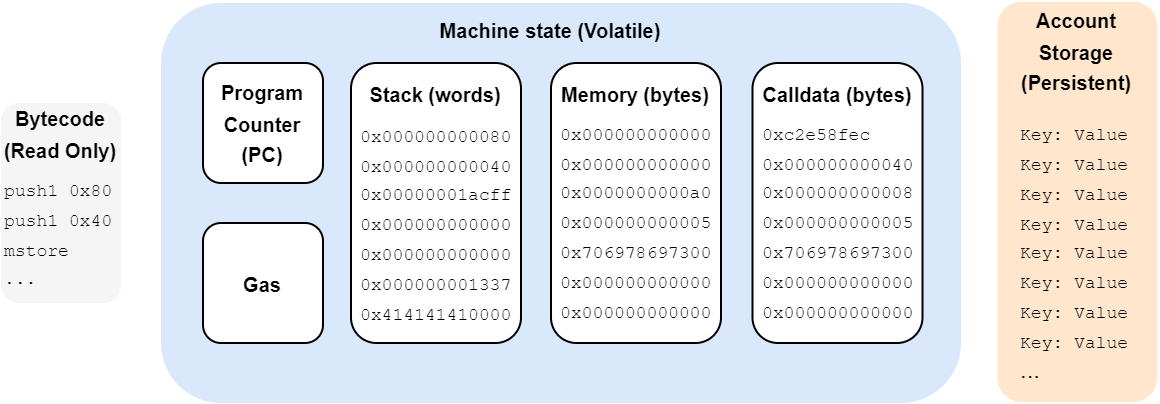

EVM memory is divided as follows:

In the article on EVM, we described the usefulness of the different memory zones and how they are arranged.

What we’re interested in in this article is account storage, the permanent storage of the smart contract’s account. It is in this storage area that the contract will record its variables, which must be persistent on the blockchain. For example, if a smart contract manages registration for an event, it is necessary for the list of registrants to be recorded, and to be able to be modified. It is typically for this type of information that acount storage is used.

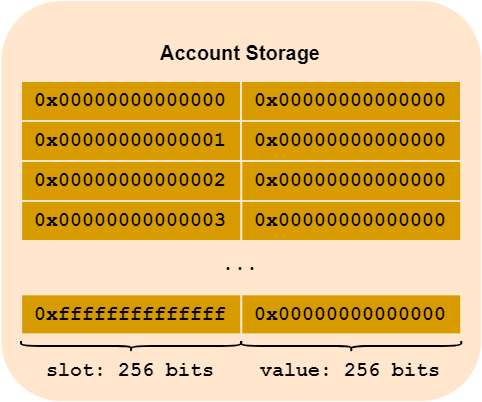

As a reminder, here’s what this memory area looks like:

It is organised into slots, which function like an index. There are 2**256 locations, and each location can store 256 bits.

If a contract (written with Solidity) wishes to store variables in this space (which we will call state variables), it must declare them outside the functions.

contract Hackndo {

/**

* State variables registered in Account Storage

*/

uint256 id = 7;

uint256 totalAmount = 1000;

/**

* Contract code

*/

constructor() {

// Code

}

function test() external {

// Local variable (not stored on the blockchain)

uint256 localVariable = 0;

}

function update() external {

id++;

totalAmount = 0;

}

}

The id and totalAmount variables will be stored in this contract’s account storage, and will be accessible by all functions in this contract. If they are updated by a function (such as update()), the contract’s account storage will be updated and these new values will be available for future transactions.

Variable visibility

With Solidity, the visibility of a variable can be defined in three different ways:

public: The variable is readable by other smart contracts. Agetteris automatically created. It can therefore be read by calling theid()ortotalAmount()function, for example.internal: The variable can only be read or modified by the contract in which it is defined, or contracts which inherit from this contract. This is the default visibility for variables.- private’: The variable cannot be read or modified by any smart contract other than the one in which it is defined.

The definitions of internal and private variables in the Solidity documentation can be confusing:

Internal state variables can only be accessed from within the contract they are defined in and in derived contracts. They cannot be accessed externally. This is the default visibility level for state variables. Private state variables are like internal ones but they are not visible in derived contracts.

If we were not careful, we might think that by defining an internal or private variable, this variable could not be read by anyone other than the contract itself, or contracts inherited from it, and that we could therefore be storing confidential information.

The internal and private variables are only private within the smart contract. However, their values can be freely read outside the blockchain by anyone, so they do not hide data in this way.

Account storage layout

As an attacker, it is then necessary to understand how variables are stored in account storage.

Storage order

The first thing to understand is that storage variables are stored by the Solidity compiler in the order in which they are declared. In the example given above, the id variable will be stored first, then the totalAmount variable.

If no value is assigned to the variable, it will take the default value 0x00, and its slot is still reserved.

When the smart contract is compiled, the compiler will try to optimise the storage space required. To do this, if variables can fit into the same 32-byte slot, they will be put into the same slot.

For example, if the state variables are as follows:

contract Hackndo {

/**

* State variables stored in Account Storage

*/

uint32 var1 = 7;

uint32 var2 = 15;

uint128 var3 = 10;

uint128 var4 = 9;

uint32 var5 = 2;

uint8 var6 = 3;

}

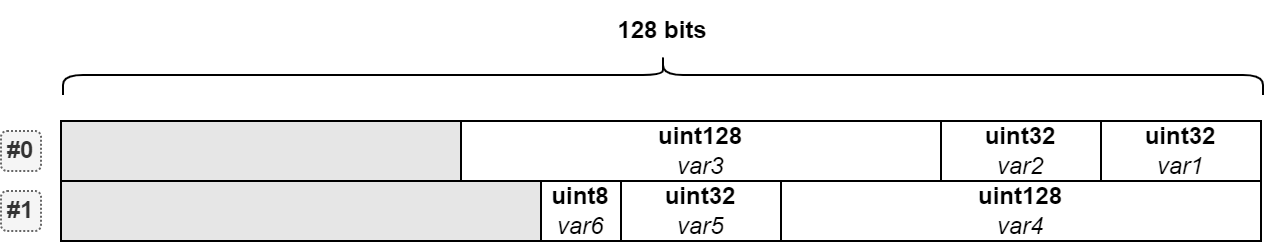

The size of a slot is 256 bits. The first 3 variables occupy 32+32+128 = 192 bits. The 4th variable cannot be added to the same slot, as there are only 64 bits available. It therefore goes into the second slot, along with the 5th and 6th variables. The size of var4, var5 and var6 is 128+32+8 = 168 bits, which fits into one slot.

This gives the following data in the storage:

# Slot 0

0x00000000000000000000 0000000000000000000000000000000a 0000000f 00000007

# empty var3 var2 var1

# Slot 1

0x00000000000000000000 0003 00000002 00000000000000000000000000000009

# empty var6 var5 var4

Constant & Immutable

With Solidity, the constant and immutable keywords can be used on state variables.

- If a variable is defined as

constant, a value must be assigned to it when it is declared, and this value can never be changed. - If a variable is defined as

immutable, it must be assigned a value, either at declaration time or in the constructor.

What these two types of variable have in common is that all uses of these variables in the code will be replaced by their value by the compiler before the bytecode is saved on the blockchain. So in fact, these notions of constant and immutable don’t exist for EVM. It’s just something practical for developers.

If, for example, we have the following contract:

contract Hackndo {

uint256 constant MAX_SUPPLY = 1000;

uint256 immutable DEST_ADDR;

constructor(address _dest_addr) {

DEST_ADDR = _dest_addr;

}

function someFunc(uint _value) {

require(_value < MAX_SUPPLY, "MAX_SUPPLY reached");

require(msg.sender == DEST_ADDR, "Not allowed");

// Some code

}

}

Two variables MAX_SUPPLY and DEST_ADDR are declared. However, they will be replaced by their values when the contract is deployed on the blockchain. So finally, if this code is deployed by address 0x1234..., it is exactly equivalent to :

contract Hackndo {

function someFunc(uint _value) {

require(_value < 1000, "MAX_SUPPLY reached");

require(msg.sender == 0x1234..., "Not allowed");

// Some code

}

}

From a bytecode point of view, constant and immutable variables don’t exist. So if you see this type of variable in a contract, you mustn’t take them into account when calculating slots.

Storing variables

Now that we’ve clarified which variables are stored in storage, and the optimisation used to limit the size of storage used, let’s look at how the different types of variable are technically stored.

Integers and Booleans

As we saw in the previous examples, integers (and booleans) are simply stored in the corresponding slot. The maximum size of an integer was 256 bits, so it can never be larger than the size of a slot, which is also 256 bits.

Table

When a array has a defined size, then its elements are stored one after the other following the rules already seen.

But a array can have a dynamic size. We are not going to change the slots of all the variables that follow the array every time the size of the array changes. Each element of the array has its own slot in which it is stored.

In this way, only the size of the array is stored in the slot that follows the rules we have described (so if a dynamic array is stored in slot 3, its size will be found in this slot).

To find the first element of the array, calculate keccak256(abi.encode(arrayIndex)) (arrayIndex would be 3 in the previous case). This result is a 256-bit hash, which corresponds to the number of the slot in which the first element of the array is located. The following elements are simply in the following slots.

Mapping

For a mapping, a slot is reserved to determine its base index, but nothing is stored there, unlike arrays where the size is stored.

To access an element in a mapping, you don’t use an index, but the element’s key to find out its value.

To determine where a mapping value is based on its key, you need to calculate the hash that concatenates the key of the element you are looking for and the slot reserved for the mapping (key + slot). The keccak256(abi.encode(key, slot)) function must therefore be applied. As with arrays, this function returns a hash, which corresponds to the slot in which the value of key is located.

String

strings of less than 32 bytes are stored in a slot. The most significant bits are used to store the string, and the least significant bits to indicate the length of the string multiplied by 2 length*2.

If it is 32 bytes or longer, then the slot reserved for the string contains the length of the string multiplied by two, plus 1, length*2+1, and the location of the string is simply the hash of the reserved slot.

For example, if a long string is supposed to be in slot 2, then the address where the string is actually located can be found with the function keccak256(abi.encode(2)).

➜ bytes32 slot = keccak256(abi.encode(2));

➜ slot

Type: bytes32

└ Data: 0x405787fa12a823e0f2b7631cc41b3ba8828b3321ca811111fa75cd3aa3bb5ace

This technique of storing double the length of the string, or double plus

1, lets you know whether you are storing a string of less than 32 bytes or more than 32 bytes. If the least significant bit of the size is1, then the string is longer than 32 bytes. Otherwise, it is less than 32 bytes. Removing this bit and dividing the size by 2 gives the actual size of the string.

Structure

Finally, the variables in a structure are stored one after the other, as if they were independent variables. If, in the structure, there are dynamic types (array, mapping etc.), then the rules we have seen apply.

Example

Here’s an example to summarise what we’ve seen so far:

// Definition of a structure

struct Coin {

string name;

uint256 price;

}

// Definition of the example contract

contract StorageContract {

uint256 constant MAX_SUPPLY = 1000;

address immutable DEST_ADDR;

uint256 totalSupply = 10;

string author = "pixis";

string description = "This is an example of storage layout made by pixis. All details in https://hackndo.com";

uint[] coinsId = [1,2,10,12];

mapping (string=>address) accounts;

Coin coin = Coin("PixCoin", 0x1000);

constructor() {

DEST_ADDR = msg.sender;

accounts["pixis"] = msg.sender;

accounts["empty"] = address(0x0);

}

}

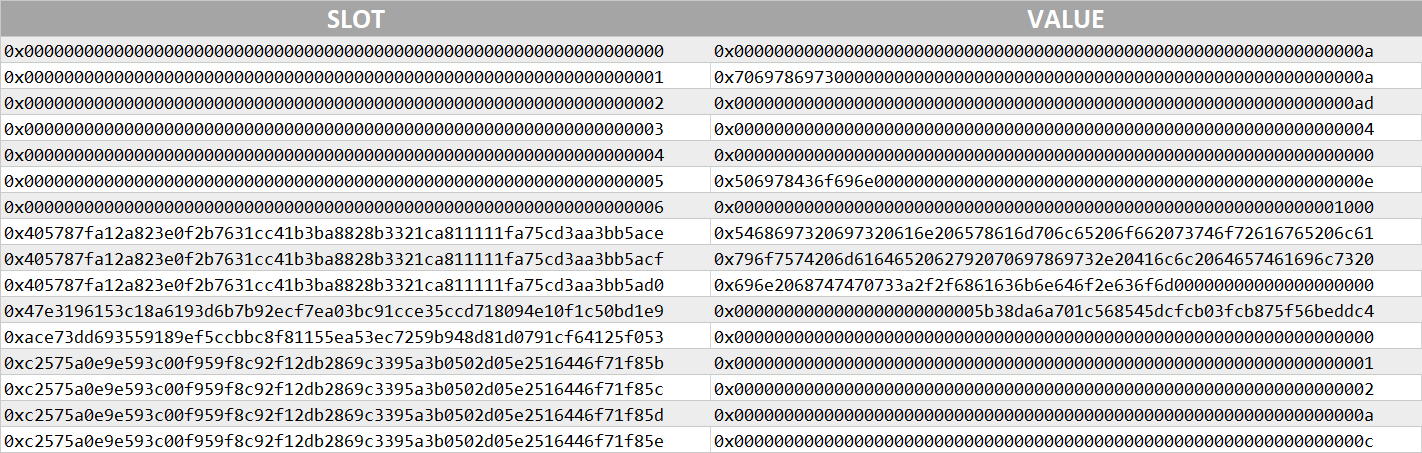

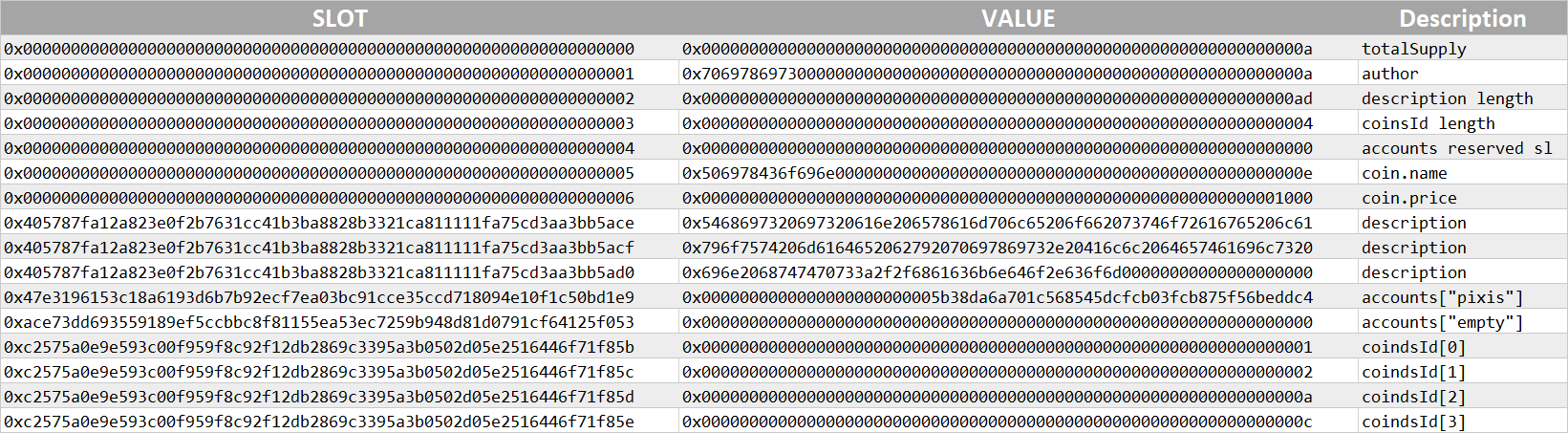

When this contract is deployed, this is what the storage looks like :

Let’s try to break this down. Firstly, the first two variables MAX_SUPPLY and DEST_ADDR are not stored in storage, so no slots are reserved for them.

Next, the following variables are assigned a slot, in the order in which they are declared.

To perform the calculations, I use chisel from the Foundry suite.

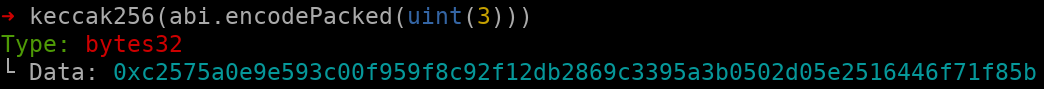

totalSupplyis a 256-bit integer, so an entire slot is reserved for it, slot0. Its value is10, so 0x0aauthoris a string of less than 32 bytes. It is therefore stored in the next slot, slot1, at the level of the most significant bits. Its size, multiplied by two (5*2 = 10 = 0x0a) is stored in the least significant bits.descriptionis a string of 86 bytes, so greater than 32 bytes. Thus, its slot2contains double its size, to which1is added (remember, by adding1, it indicates that the string is longer than 32 bytes), so86*2+1 = 173 = 0xad. The slot containing the string corresponds to the hash of the string’s slot, so2. Howeverkeccak256(abi.encode(2)) = 0x405787fa12a823e0f2b7631cc41b3ba8828b3321ca811111fa75cd3aa3bb5aceso the slot0x405787fa12a823e0f2b7631cc41b3ba8828b3321ca811111fa75cd3aa3bb5acecontains the string.coinsIdis an array containing 4 elements. Its size0x04is therefore specified in its slot3. The slots of these 4 elements are calculated as follows:- Index 0:

keccak256(abi.encode(3)) = 0xc2575a0e9e593c00f959f8c92f12db2869c3395a3b0502d05e2516446f71f85b. For the other elements, the slot is incremented by 1 each time. - Index 1:

0xc2575a0e9e593c00f959f8c92f12db2869c3395a3b0502d05e2516446f71f85c - Index 2:

0xc2575a0e9e593c00f959f8c92f12db2869c3395a3b0502d05e2516446f71f85d - Index 3:

0xc2575a0e9e593c00f959f8c92f12db2869c3395a3b0502d05e2516446f71f85e

- Index 0:

accountsis a mapping whose slot is4. It’s noticed that this slot is empty, that’s normal. The size of the mapping is not stored. To find the value of a particular key, the functionkeccak256(abi.encodePacked(key, slot))should be used so:accounts["pixis"]is found at the slotkeccak256(abi.encodePacked("pixis", uint(4))) = 0x47e3196153c18a6193d6b7b92ecf7ea03bc91cce35ccd718094e10f1c50bd1e9accounts["empty"]is found at the slotkeccak256(abi.encodePacked("empty", uint(4))) = 0xace73dd693559189ef5ccbbc8f81155ea53ec7259b948d81d0791cf64125f053

coinis a structure containing two elements. They are therefore positioned in the slots5(name, less than 32 bytes) and6(price, worth0x1000).

With all these explanations, we are able to understand the entire account storage of this contract, once deployed.

Memory reading

It’s great, we are able to read and understand the storage space of contracts, but concretely, how do we access the storage space of a contract already deployed on the blockchain?

Different tools allow reading the slots of a contract’s storage. Personally, I use the cast tool from the foundry suite.

Indeed, when you install foundry on your machine, different tools are installed:

- Forge: Framework for performing tests on Ethereum

- Cast: Tool for interacting with smart contracts and the blockchain

- Anvil: Local Ethereum node

- Chisel: REPL tool for quickly executing Solidity code

The cast tool is very handy for reading a contract’s slots. The syntax is as follows:

cast storage 0xcontract_address slot_number [--rpc-url RPC_URL]

For example, to read the slot 0 of the contract at address 0x099A3B242dceC87e729cEfc6157632d7D5F1c4ef on Ethereum (random contract), the following command line can be used:

cast storage 0x099A3B242dceC87e729cEfc6157632d7D5F1c4ef 0 --rpc-url https://eth.llamarpc.com

0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

So, the value 0x01 is in slot 0 of the contract. We can loop to read the first 6 slots:

for I in {0..5}

do

echo "SLOT $I: " $(cast storage $CONTRACT_ADDR $I --rpc-url $RPC_URL)

done

SLOT 0: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

SLOT 1: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

SLOT 2: 0x00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000c6645100000000

SLOT 3: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000205

SLOT 4: 0x000000000000000000000000000000000000000003f806d77433774f8c683600

SLOT 5: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000c6647c

Putting it into practice

A contract is deployed at address 0x84229eeFb7DB3f1f2B961c61E7CbEfd9D4c665E3 on the Sepolia test network.

This contract is a game whose code is:

pragma solidity ^0.8.9;

contract GuessingGame {

address public owner;

mapping(address => bool) public hasGuessed;

uint256 private secretNumber; // Declared as private. Is it really private?

constructor() {

owner = msg.sender;

secretNumber = 12345; // This is not the real number

}

function guess(uint256 _number) public {

if (_number == secretNumber) {

hasGuessed[msg.sender] = true;

}

}

function isWinner(address _addr) public view returns (bool) {

return hasGuessed[_addr];

}

}

The goal is to call the function guess() by providing a number. If you hit the right number, you win, and you can prove it with the isWinner() function.

As we have seen in this article, the variable secretNumber has been declared as private, but that will not prevent us from retrieving this value. For this, let’s use the cast tool.

To encourage you to try, the result provided below is not the real result. It’s up to you to find the real secret value! The logic remains the same.

RPC_URL=https://rpc2.sepolia.org

CONTRACT_ADDR=0x84229eeFb7DB3f1f2B961c61E7CbEfd9D4c665E3

for I in {0..3}

do

echo "SLOT $I: " $(cast storage $CONTRACT_ADDR $I --rpc-url $RPC_URL)

done

# Output

SLOT 0: 0x00000000000000000000000031d6273610256e6cefd6f26a503c72bb2bdcfe15

SLOT 1: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

SLOT 2: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000042424242

SLOT 3: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

We see that the first three slots are used. The first corresponds to the first state variable, that is the owner address. The second variable seems empty, but that’s normal. This is the slot used by the hasGuessed mapping.

secretNumber is recorded in the 3rd slot, and its value is 0x42424242.

Congratulations, you have discovered a secret variable in a contract deployed on an Ethereum network!

To interact with the contract, still with the cast utility, here’s how to proceed:

# To create a transaction, we use cast send

# To be able to sign the transaction, the private key must be provided.

cast send $CONTRACT_ADDR "guess(uint256)" "10" --private-key 0xabcdabcd...abcd --rpc-url $RPC_URL

# To read information without modifying the storage, we use cast call.

# isWinner() writes nothing in the storage, so no need to give it a private key. It's just information reading.

# If the output is 0, your address has still not found the right number.

# If the output is 1, congratulations, you have found the secret number!

cast call $CONTRACT_ADDR "isWinner(address)" "your address" --rpc-url $RPC_URL

It’s your turn to play!