Ethereum Virtual Machine

Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) is a virtual machine used to manage transactions on the Ethereum blockchain via smarts contracts. It’s an essential component of Ethereum, which we’re going to try and understand together.

EVM

To execute smart contracts (programs in Ethereum’s world), rules must be followed. These rules are partly described in Ethereum’s Yellow Paper, and can be implemented by anyone in any language. There is a python version of EVM (py-evm), a Rust version (revm), and a Go version (go-evm). This list is by no means exhaustive.

Opcodes

One of EVM’s key features (like any computer) is the ability to read and execute instructions, or opcodes. Ethereum instructions are described on the official Ethereum website, Opcodes for the EVM. The website evm.codes is also very useful.

This is the kind of code that is understood by the EVM. It is generated when a high-level language is compiled. One of the most widely used languages for writing smart contracts is Solidity.

Here’s a very simple example of a smart contract written in Solidity.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity 0.8.18;

contract HackndoMembers {

// Declaring persistent variables in the blockchain

address public owner;

address[] public members;

uint private memberCount;

// Constructor, executed when smart contract is deployed

constructor() {

owner = msg.sender;

}

// Public function to register as a member

function becomeMember() external {

members.push(msg.sender);

memberCount++;

}

// Public function to find a member

function getMember(uint _id) external view returns(address member) {

require(_id < memberCount, "id too big");

require(members[_id] != 0x00, "Not a member");

member = members[_id];

}

// Function only available to the smart contract creator to delete a member

function removeMember(uint _id) external {

require(msg.sender == owner, "Owner only");

members[_id] = address(0x0);

}

}

Once compiled, this program will be a sequence of instructions, or opcodes, understood by the EVM. The solc tool can be used to compile Solidity.

$ solc contract.sol --bin

======= contract.sol:HackndoMembers =======

Binary:

608060405234801561001057600080fd5b5033600080610100[...]

It also shows the generated opcodes.

$ solc contract.sol --opcodes

======= contract.sol:HackndoMembers =======

Opcodes:

PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH2 [...]

Some of these instructions are used to execute mathematical operations, such as add, sub, mul or div. Others are used to compare elements, such as lt (Lower Than), gt (Greater Than) or eq.

It is possible to read from and write to different storage areas, such as memory with mLoad, mStore, or storage with sLoad, sStore for example.

The stack (another memory area) is managed with opcodes such as push1, push2, …, push32, and pop.

These different types of storage will be discussed later in this article.

A contract can make calls to other functions, potentially other contracts, via call, staticcall and delegatecall.

Finally, the revert instruction can be used to make a kind of exception that terminates the current call. In most cases, the transaction will be considered invalid, and no changes will be made.

These examples are by no means exhaustive, but they give an idea of what the EVM has to deal with when a smart contract is executed.

Gas

Each instruction executed on the nodes has a price, the unit of which is the gas. For example, executing an add costs 3 gas, while a pop costs just 2.

When calling a smart contract function, a user must pay the price required to execute the instructions. He must therefore provide sufficient gas during his transaction. If he has supplied too much, it’s no problem - the remaining gas will be refunded.

If, on the other hand, he has not supplied enough, the instructions will be executed until the gas is exhausted. When this happens, the transaction is cancelled, and the gas supplied by the user is lost. Although the transaction is cancelled, it still took resources to detect it, so it’s too late.

This notion of gas was introduced to prevent resources from being used unnecessarily, in particular to avoid infinite loops or attacks that would clog up the network. In fact, there is a maximum number of gas possible in a single block (currently 30 million gas).

Solidity

For the rest of this article, bear in mind that EVM, in the end, just executes opcodes, one after the other. It also offers various empty storage spaces that can be used, and that’s it. How these opcodes are organized, or how the data is structured, is up to the compiler.

What we’re going to look at in this article concerns the Solidity compiler (and language). Other language compilers often use Solidity as a reference and follow the same conventions, but this is not always the case.

Global variables

When a smart contract is written with Solidity, there are three global variables accessible to the smart contract, providing information about the context in which it is executed:

- Block (

block): This variable contains information about the block in which the transaction was validated. This includes the block number, the time it was added to the blockchain, and its hash. - Transaction (

tx): Information relating to the current transaction is available in this variable. This is where we’ll know, for example, who initiated the transaction (who may be different from who initiated the last message), so it will always be an EOA. - Message (

msg): Several messages can be sent within a transaction. In these messages, you can find out who sent the message, how many Ethers were supplied, the data included in the message, and so on. Depending on the context and the message, themsgvariable may change. For example, when a contract calls another contract, themsg.senderattribute will be modified.

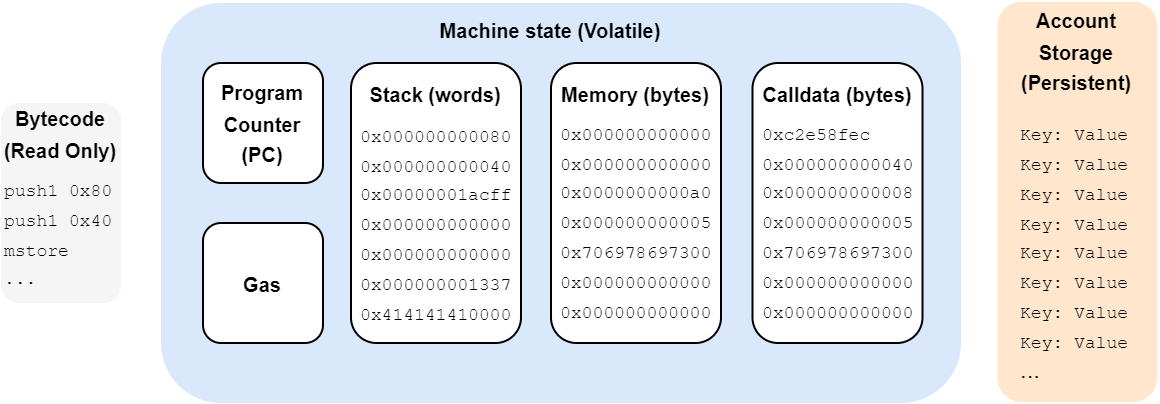

Storage

The smart contract code (made up of opcodes such as the ones we’ve introduced) needs to be stored somewhere, as do the contract variables and other temporary or permanent data required for proper execution. For this purpose, the EVM has various types of storage, permanent or not, for different purposes.

Permanent storage

There are two types of persistent storage. These are the places where information is stored by nodes, and persistent during transaction execution. So, when a transaction is completed, this storage will be saved, and can be used for the next transaction. How convenient!

Bytecode

The smart contract code is permanently stored, but cannot be modified. It’s read-only. If an issue is detected in the smart contract after it has been deployed, it’s too late. You have to deploy a new smart contract with its fix, and warn users that the smart contract address has changed.

There are ways of dealing with this problem with proxy smart contracts, but that’s not the topic, and these contracts can also have bugs.

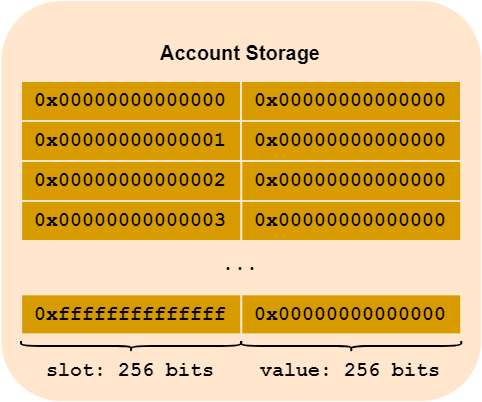

Account storage

The persistent storage location for smart contracts is account storage. It’s a bit like a computer hard drive. We talked about this in Ethereum article. In the world state (Ethereum’s global state), each address is associated with various elements, such as the account’s Ether balance, but also, in the case of smart contracts, a “storage space” specific to the smart contract.

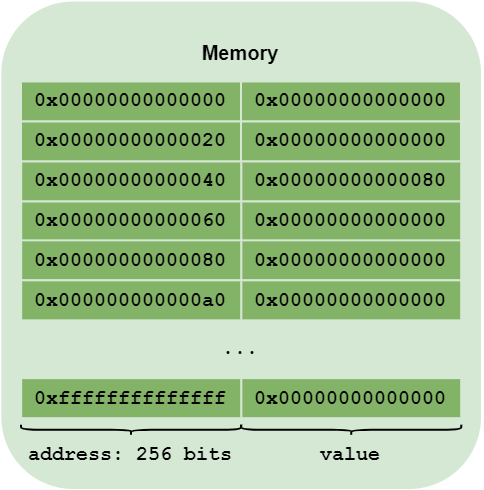

In practical terms, this account storage is a key/value database. The key is a 256-bit value, and so is the value. We can therefore store 2**256 keys, which should be more than enough. For the sake of clarity, we can also think of this storage as an array of 2**256 rows, and each row can be assigned a 2**256 bits value.

Before anything is executed, this array is empty - it’s all zeros. So each contract has, by default, an array of 2**256 lines, and each line has 2**256 bits set to zero.

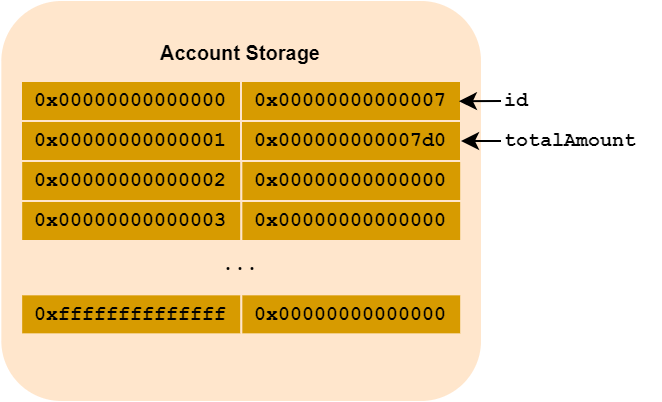

Generally speaking, the first slots (or rows) of a Solidity contract contain the contract’s state variables.

Let’s take the following example:

contract Hackndo {

/**

* State variables

*/

uint256 id = 7;

uint256 totalAmount = 1000;

/**

* Contract code

*/

constructor() {

// Code

}

function myFunction() external {

// Code

}

}

Once the contract has been created, the account storage will contain the following key/values:

When referring to a key, the term slot is often used. In the following example, slot 0 is the

idvariable and slot 1 is associated with thetotalAmountvariable.

Optimisation

The declared variables were uint256, i.e. 256 bits, which took up an entire slot, but if smaller variables are used, the storage will be optimized by the Solidity compiler. If two variables fit into one slot, then they will be put into that same slot. We’ll see this in details in another article.

Other types

In this account storage area, you can store not only integers, but also strings, arrays, mappings and so on. Each type of variable has its own storage rules, which are managed by the Solidity compiler so that they can be retrieved. Here’s a quick overview:

When a array is stored, the size of the array is stored at an index which follows the previous rule. To find the array Nth element, you need to compute keccak256(abi.encode(arrayIndex))+N.

keccak256is a hash function (old SHA3 version).abi.encodeis used to encode information in order to transform potentially complex data structures (such as arrays) into a sequence of bytes, enabling a hash function to work correctly.

For a mapping (a key-value association), a slot is reserved to determine its base index (but nothing is stored there, unlike arrays for which the size is stored), then to determine where a value in the mapping is located, the function keccak256(abi.encode(key, mappingIndex)) must be applied. It returns the index where the key value is located.

strings of less than 32 bytes are stored in a slot. The most significant bits are used to store the string, and the least significant bits to indicate its length. If it’s 32 bytes or longer, then the same mechanism as for arrays applies.

Finally, variables in a structure are stored one after the other, as if they were independent variables. If, in the structure, there are dynamic types (array, mapping etc.), then the rules we’ve seen apply.

Volatile storage

Volatile memory is memory which, once the contract has been executed, is erased, leaving no trace of it. You could compare this memory to RAM (random access memory) in a computer.

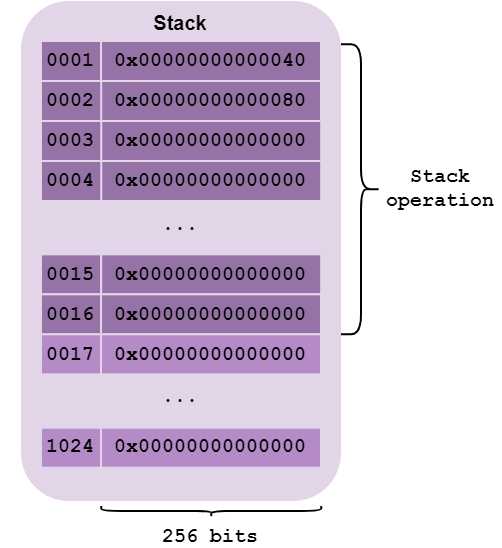

Stack

The stack is a LIFO (Last In, First Out) memory location.

This means that the last element pushed on the stack will be the first element to be unstacked. To better understand this, imagine a stack of plates. If you stack plates on top of each other, you’ll have to remove the last plate placed on top, then the second-to-last plate, etc., before you can retrieve the first plate placed on top.

This memory area is used by the compiler to store temporary information, such as a function’s local variables, or opcodes arguments, for example. Typically, all smart contracts compiled with Solidity start with these 3 instructions to store the value 0x80 at memory address 0x40.

PUSH1 0x80 // destination

PUSH1 0x40 // value

MSTORE // mstore(destination, value)

mstore function arguments are pushed onto the stack in the reverse order of their use. In fact, the first element to be popped will be the last element pushed. So, first the value 0x80 is pushed, then the destination 0x40. When mstore is executed, 0x40 (the destination) will be popped, followed by 0x80 (the value).

This is a memory area that changes a lot as a program is executed. Up to 1024 elements of 256 bits (32 bytes) can be stored here.

Please note that only the first 16 elements of the stack can be used to perform operations, call functions, etc. This means, for example, that a function cannot have more than 16 arguments, or more than 16 local variables.

Memory

The memory of a smart contract is a large memory area accessible for reading and writing in no predefined order, unlike the stack. It can store any size of information, from one byte up to 32 bytes at a time. On the other hand, information can only be read by 256 bits (32 bytes). This is where you’ll find variables with dynamic sizes, such as arrays or mappings, but you can also store integers or Booleans.

Addressing is done on 32 bytes. So, theoretically, you can store up to 2**256 bits of information. In practice, this is mainly to avoid collisions when storing dyamically-sized data. We use the hash of certain elements to decide on the storage destination. There’s plenty of time to win the lottery before two hashes in a 2**256 space are close!

Reserved space

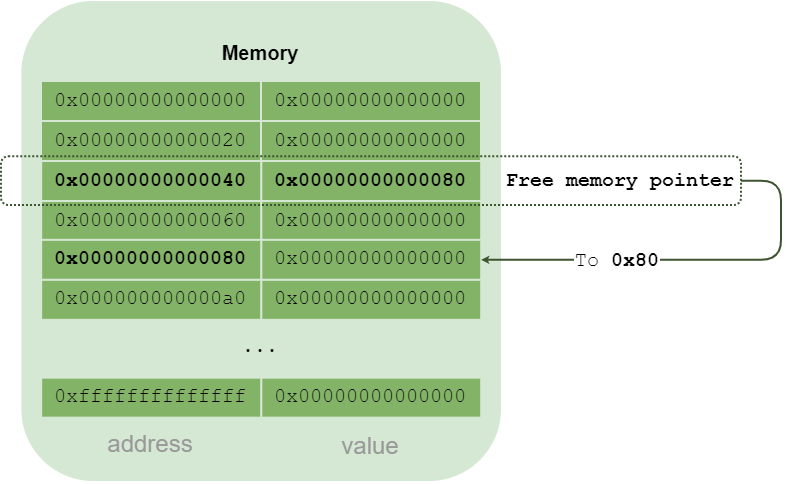

The first two bytes (at addresses 0x00 and 0x20) are used by the compiler to perform temporary calculations or operations.

The third location (0x40) contains a pointer to the next free, usable memory area. This is the free memory pointer.

In fact, it is this pointer that is initialized at the start of every contract compiled with Solidity as we saw earlier in this article. The following operations store 0x80 at address 0x40.

PUSH1 0x80

PUSH1 0x40

MSTORE

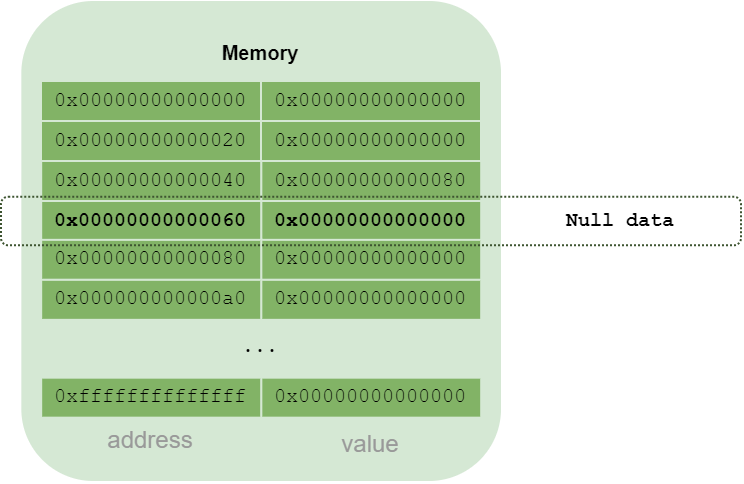

So the next area free for memory allocation is located at address 0x80. And why not address 0x60? Because this address is also special: it’s always 0. It can be copied to initialize an array, for example.

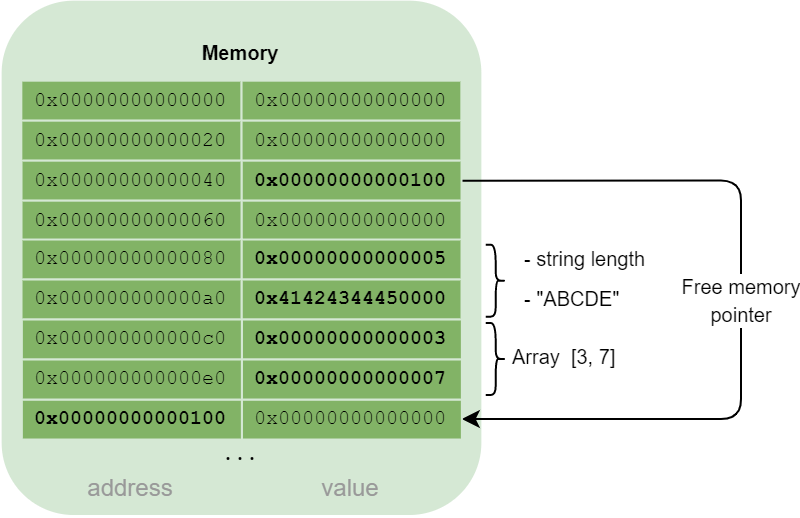

Data storage

Simple formats such as integers are simply stored at the address assigned to them.

For strings, when an address is assigned to store them, the length of the string is stored in the 256 bits starting at that address, then the string is stored.

For arrays, a placeholder corresponding to the number of elements is reserved, and the array elements are added one after the other.

A structure is organized in the same way as an array.

Calldata

When calling a smart contract function, the call must be created by the client before sending the transaction, i.e. before the EVM is instantiated anywhere. The function’s parameters cannot therefore be in a stack or in the EVM’s memory.

The function, and its arguments, are sent in the data field of the transaction, as we briefly saw in the article on Ethereum. When the contract is actually instantiated and executed in the Ethereum virtual machine, what has been sent in data will be copied into the memory area called calldata.

This memory area, calldata, is used when an Ethereum client calls a function, but not only. It is used every time a message is sent, whether from an EOA to a contract, or from a contract to a contract.

From a memory point of view, calldata is very similar to memory.

- It is linear

- Addressing is byte-by-byte.

- Only 32 bytes can be read per call.

However, unlike memory, this memory area is read only. It cannot be written to. The EVM is responsible for copying the parameters sent by the message source.

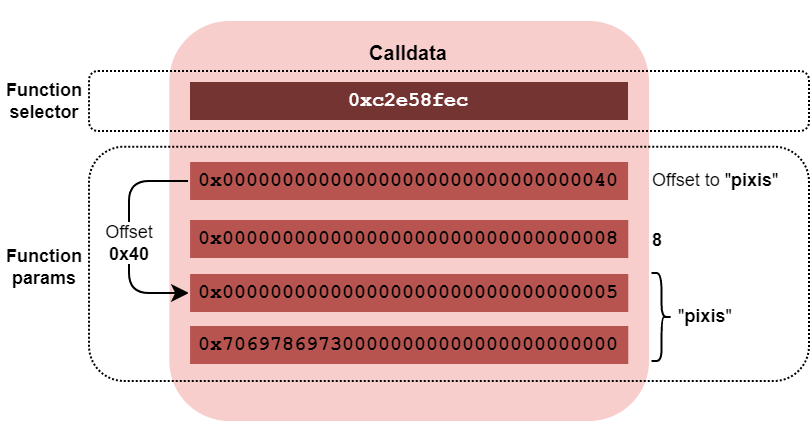

Function selector

The first 4 bytes are reserved for the function selector. As explained in the article on Ethereum, the function selector is calculated by hashing the function signature, and keeping only the first 4 bytes.

For example, let’s take the following function:

function getItemValue(string calldata _itemName, uint256 _itemId) public returns(uint256 value) {

// Function code

}

Function signature is:

getItemValue(string,uint256)

And its selector:

bytes4(keccak256("getItemValue(string,uint256)"));

// Output:

0xc2e58fec

The rest of this memory area is dedicated to function arguments.

Function arguments storage

Simple formats such as integers are stored as is.

For strings, we store the offset of where the string actually is. This offset is used to find the string, starting with its size (on 256 bits) and then the string itself.

For arrays, similarly, we store the offset where the array is located. This offset is then used to store the array elements.

A structure is organized in the same way as an array.

Let’s take the same example as in the previous article about Ethereum:

getItemValue("pixis", 8);

calldata value will be:

0xc2e58fec0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000040000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000800000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000057069786973000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

This can be broken down as follows:

PC - Program Counter

For the record, there’s also a memory area called the Program Counter or PC. For those familiar with the Intel world, this is the equivalent of “EIP” (or “RIP”) register. It’s a memory area containing the address of the next instruction to be executed. It allows the virtual machine to know where to execute the next opcode. Often, this address increases little by little, and sometimes, when there’s a jump, the destination of the jump is assigned to the PC, so that the next instruction executed will be the jump destination.

Gas

Finally, the EVM keeps track of the number of consumed gas, to check that there is sufficient gas supplied by the user.

Calls

Having reviewed the different memory zones that enable the EVM to run, we’ll finish by talking about the different types of calls that can be made to a smart contract to execute code. These calls are used to execute a smart contract function, with arguments if necessary.

Each type of call has its own specificities. To understand what we’re talking about, we first need to explain that a contract is executed in a certain context. Sometimes, when a function is called, a new instance of EVM is deployed to execute the function code. Sometimes the memory areas are different, sometimes shared. Global information (such as the message source) may or may not also vary, depending on the type of call.

We’ll summarize the details of each call in a table below.

Internal calls

The simplest are internal calls. This is what happens when a smart contract calls one of its own functions, or a function from a contract it inherits. In opcode terms, when an internal call is made, a jump is executed. There is no change of context, we remain in the same contract, in the same virtual machine instance. The called function shares the same information and storage areas as the calling function.

Here are two examples of internal calls, one for a function from the same contract (functionA()) and the other calling a function from a parent contract (functionParent()).

contract Parent {

function functionParent() internal pure {

}

}

contract Child is Parent {

function functionA() internal pure {

}

function functionB() external pure {

// Internal call to a function within the same contract

functionA();

}

function functionChild() external pure {

// Internal call to a function in the inherited contract

functionParent();

}

The contents of functionA() could have been put into functionB(), it wouldn’t have made much difference.

External calls

External calls are more interesting. They allow you to call functions from other contracts. There are 3 different types of external call.

In fact, there’s a 4th,

callcode, but it’s been deprecated in favor ofdelegatecall, so we won’t talk about it here.

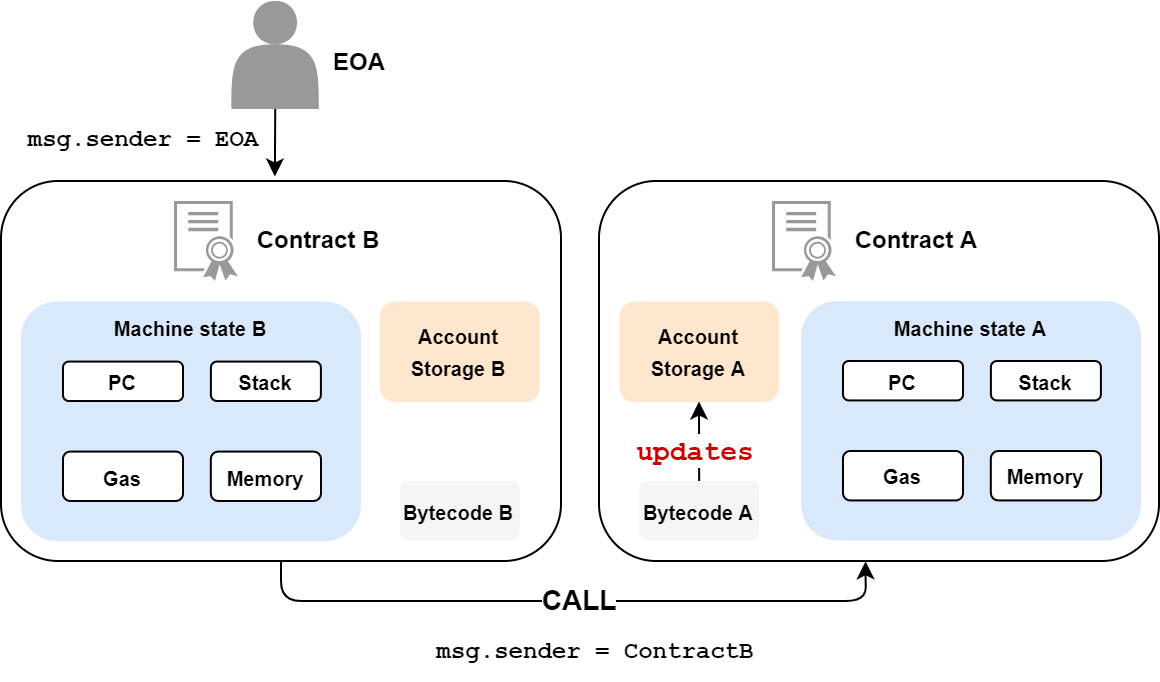

call

The call opcode is the basic call. It allows you to call a function from another contract. This function will be executed in a new EVM instance, with its own memory zones (stack, memory, etc.). The called code can then do as it wishes, modify its own memory, update its variables, etc. Understand, however, that the variables of the called contract are completely independent of the variables of the calling contract. Good fences make good neighbors.

In addition, message data is updated. Thus, the originating address (msg.sender) becomes that of the calling contract, and the value included in the message (msg.value) is also updated.

You can also send Ethers via a call.

Here’s an example:

contract ContractA {

uint public callCounter;

function functionA() external payable {

callCounter++;

}

}

contract ContractB {

ContractA contractA = new ContractA();

function functionB() external {

// call because functionA modifies information in storage, in this case its "callCounter" variable

contractA.functionA();

}

}

It is possible to use the call function explicitly, as follows:

(bool success,bytes memory data) = address(contractA).call{value: 0.1 ether}(abi.encodeWithSignature("functionA()"));

The call will return a boolean status on the successful execution of the call as well as the data optionally returned by the called function. Note also that, in this example, we have sent 0.1 ether to the called contract.

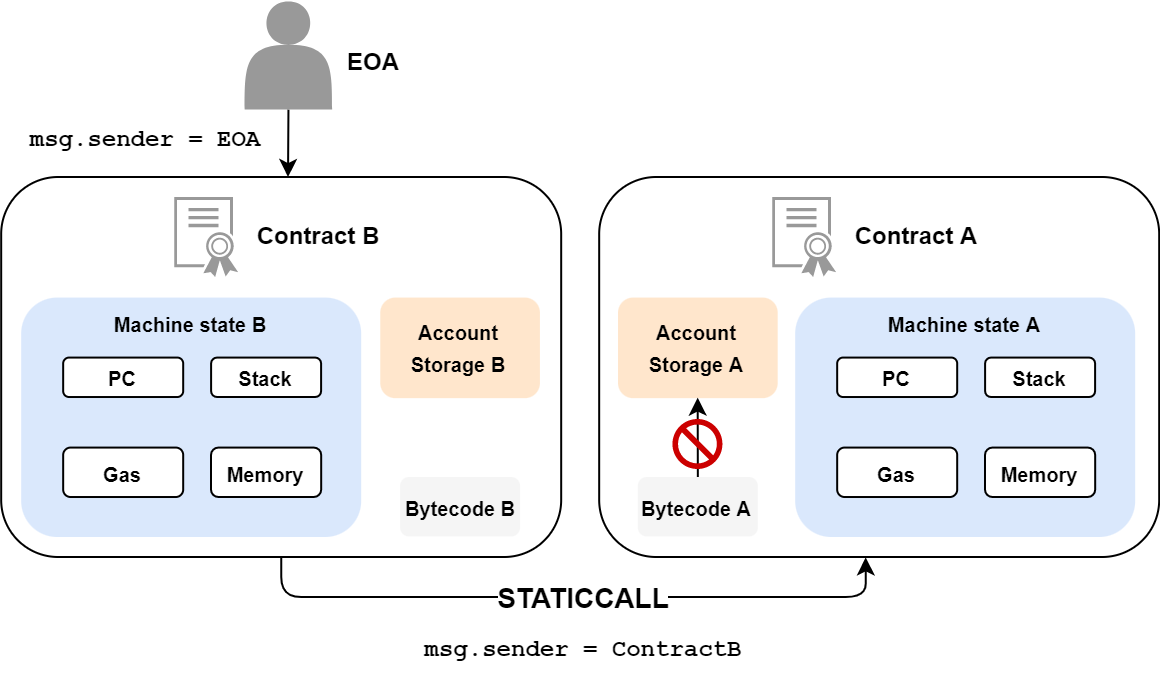

staticcall

staticcall is in every respect similar to call, but the function called cannot make any modifications to the blockchain, neither its storage nor its ether balance. It’s a kind of read-only call.

contract ContractA {

function functionA() external view {

// Some code

}

}

contract ContractB {

ContractA contractA = new ContractA();

function functionB() external view {

// staticcall because functionA is declared as "view", so it won't modify its storage

contractA.functionA();

}

}

As this call cannot modify the blockchain, the balance of the called contract cannot be modified. It is therefore not possible to send Ethers via this call. It is also possible to call the staticcall function explicitly, as follows:

(bool success,bytes memory data) = address(contractA).staticcall(abi.encodeWithSignature("functionA()"));

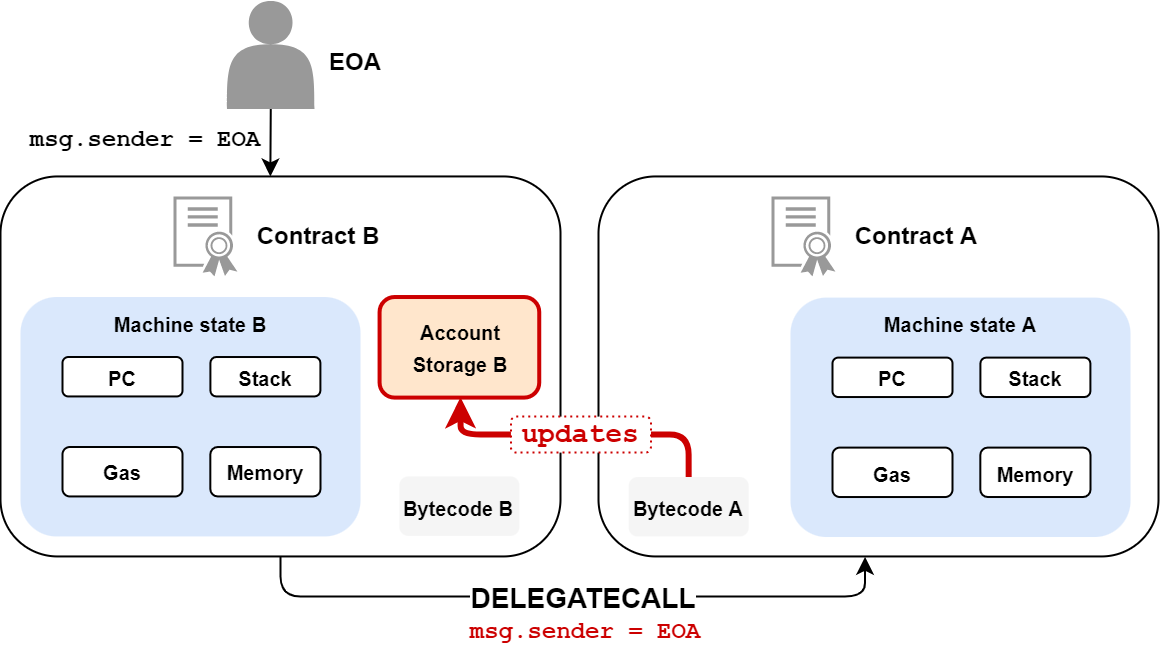

delegatecall

The delegatecall call is very special. It can be extremely useful, but also extremely dangerous. Whereas with the call and staticcall calls, the memory areas were clearly separated between the caller and the called party, this is not completely the case with the delegatecall call.

In this case, all volatile memory areas (stack, memory, PC) are specific to the called contract, contract B, however:

- The reads and writes to storage will be done in the storage of contract A.

- The message origin address (

msg.sender) and value (msg.value) will not be updated. So if an EOA calls contract A, and contract A performs adelegatecallto contract B,msg.senderwill still be the EOA when contract B executes its code.

contract ContractA {

uint private secretNumber;

function updateSecret() public payable {

secretNumber = 1337;

}

}

contract ContractB {

uint private secretNumber = 42;

ContractA contractA = new ContractA();

function callContractA() public payable {

// B's storage is updated because of the delegatecall

(bool success, bytes memory data) = address(contractA).delegatecall(abi.encodeWithSignature("updateSecret()"));

}

function getSecretNumber() external view returns(uint) {

return secretNumber;

}

}

In this example, ContractB has a private storage variable, secretNumber, equal to 42. By performing a delegatecall to ContractA, ContractA will update the secretNumber variable. This update is made in ContractB’s storage. So, following this call, the getSecretNumber() function will return 1337, not 42.

A classic use case for this type of call is proxy contracts. When a developer wants to update his contract, he has to deploy it again, and provide his users with the new address.

One solution is to create a proxy contract, in which all application information is stored, and this contract performs delegatecall to the real application. The developer communicates the proxy address to all his users.

If one day, the application needs to be updated, all that’s needed is to call a specific function in the proxy to update the application’s address. This update is transparent to users, since the proxy has not been modified.

Calls summary

Here’s a small table summarizing the different types of call.

| Call from contract A to contract B | New EVM instance | Storage | msg.sender/msg.value | Blockchain state update |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| call | Yes | Contrat B | Updated | Possible |

| staticcall | Yes | Contrat B | Updated | Impossible |

| delegatecall | Yes | Contrat A | Not updated | Possible |

Conclusion

This article has given us an overview of the EVM, Ethereum Virtual Machine. The virtual machine executes opcodes, within the limit of the gas sent by the user, since code execution has a cost.

To function properly, the EVM uses different memory areas to store temporary and persistent information.

Lastly, so that contracts can call each other, different calls are supported by the EVM.

These basics should be enough for us to take a serious look at smart contract vulnerabilities in future articles.