Blockchain 101

For several years now, I’ve been interested in a subject you’ve probably heard of: blockchains. I find it fascinating that a technology allows thousands of people to agree on so many subjects without the need for an intermediary. Decentralization is a subject that I believe has a lot of potential, and we’ll see in the long term whether this technology will endure or not. In any case, as it stands, it’s a hot topic! More recently, I’ve become interested in the Ethereum blockchain, smart contracts, and the security of smart contracts. We’re going to talk about all that here, here we go.

Before diving into the security of smart contracts, it’s important to recap some key concepts about blockchains. What is it, how does it work, who are the actors involved, we’ll look at all this in this introduction article. The idea is not to go into all the details, but to get an overview of how blockchains work in general. As the technical specifics vary greatly from one blockchain to another, we’ll cover them in due course in future articles.

Definition

There are hundreds of definitions for the term blockchain. What I think is important to understand is that it represents a decentralized registry (or database). There is no central entity deciding whether a transaction is valid or not, but rather thousands of people or machines working to verify and validate these transactions, all driven by mathematical rules and concepts.

In a nutshell, we can simplify a blockchain by imagining it as a huge Excel spreadsheet in which you can add rows one after the other. It is also possible to read the entire Excel file, from the moment it was created. However, it is not possible to modify a line that has already been written and validated. It’s append only.

Of course, this is a simplification, as blockchains such as Ethereum include, in addition to classic transactions, a virtual machine with its own storage space and so on. We’ll talk about this in the next article.

Transactions

What are these transactions? They are simply transfers of coins from one account to another. If Alice wants to send 1 coin to Bob, that’s a transaction.

A coin is the cryptocurrency of the blockchain. For the Bitcoin blockchain, it’s Bitcoin, for the Ethereum blockchain it’s Ether, for Solana it’s Sol, and so on.

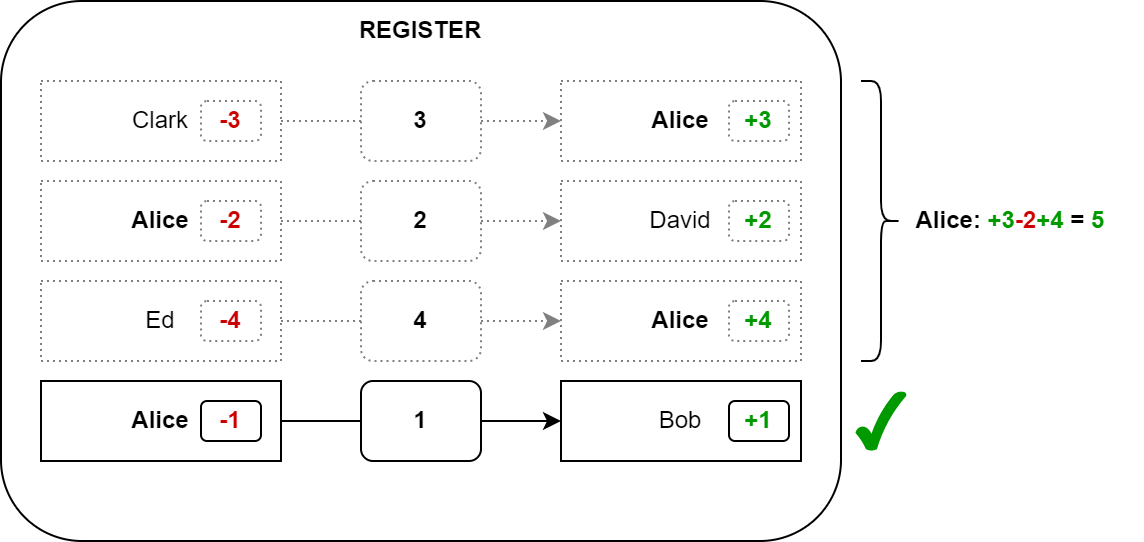

To find out if Alice has enough coins, all you have to do is read the transaction history. The whole history. If one day she received 3 coins, spent 2 of them, then received 4, we can know, at the current time, that Alice has 3-2+4, i.e. 5 coins. She is then entitled to spend 1 coin, so everything’s fine.

Note that this is how Bitcoin works, but for other blockchains, the balance of each account is sometimes kept up to date (in the blockchain or not) to avoid having to recompute users’ balances for each transaction.

Here’s what a classic blockchain contains. A record of all users’ spending since the blockchain was created.

User

To be a blockchain user, you need to have a pair of asymmetric keys: a public key and a private key. The private key, obviously carefully stored by each user, is used to sign all transactions. This is how, when Alice claims to be sending 1 coin to some address, it is possible to verify that it was Alice who initiated the transaction. She has signed it with her private key, and anyone can check that this signature is valid with her public key.

This means that in a blockchain, we don’t know that the user is Alice. Rather, a user is defined by an address (derived from the public key). So when Alice wants to execute a transaction, from the blockchain’s point of view, her address is the source of the transaction.

Furthermore, to communicate with the blockchain, the user will use a client. This is nothing more than a program that knows how to generate transactions, communicate with the network and so on. The user could code everything himself, but that’s not practical. It’s a bit like using a web browser to go online. It’s more practical than writing code to make HTTP requests.

Validation

That’s all very well, but who validates these transactions? Who does the math to verify that Alice has at least 1 coin to send to someone? And checks that it’s really Alice who’s doing the transaction?

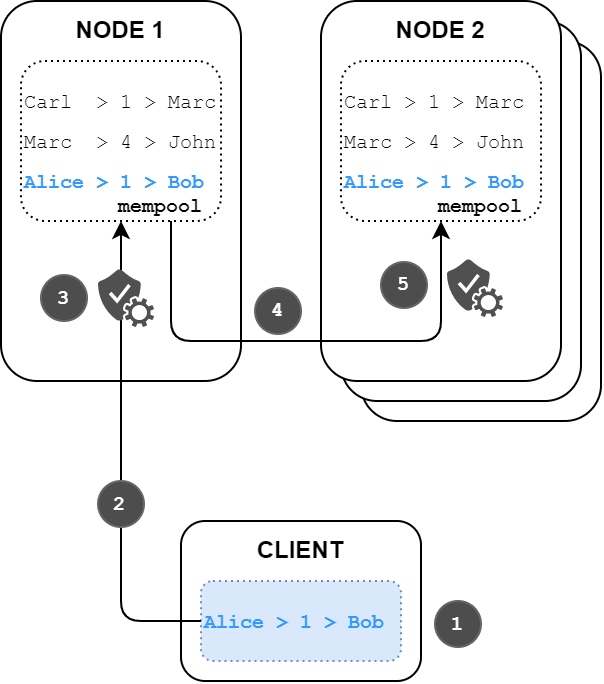

This is where the concepts of blocks and validators come in. For a blockchain to work properly, several people need to get to work validating transactions. They create so-called nodes, which will be able to broadcast themselves to the network and become part of it, retrieving past transactions and those awaiting validation. It’s a true peer-to-peer network. As soon as a user wants to send a transaction (1), the client he is using to send his transaction will notify another node (via NewPooledTransactionHashes) that a new transaction has been sent (2). The transaction will be verified (signature verification, funds available, etc.) (3), but it is not yet validated. It will join the waiting list of transactions that have been sent but not yet validated, called the mempool. This node will also notify other nodes by broadcasting this transaction (4), and these new nodes will do the verification work themselves (6) and add this transaction to their mempool, and so on.

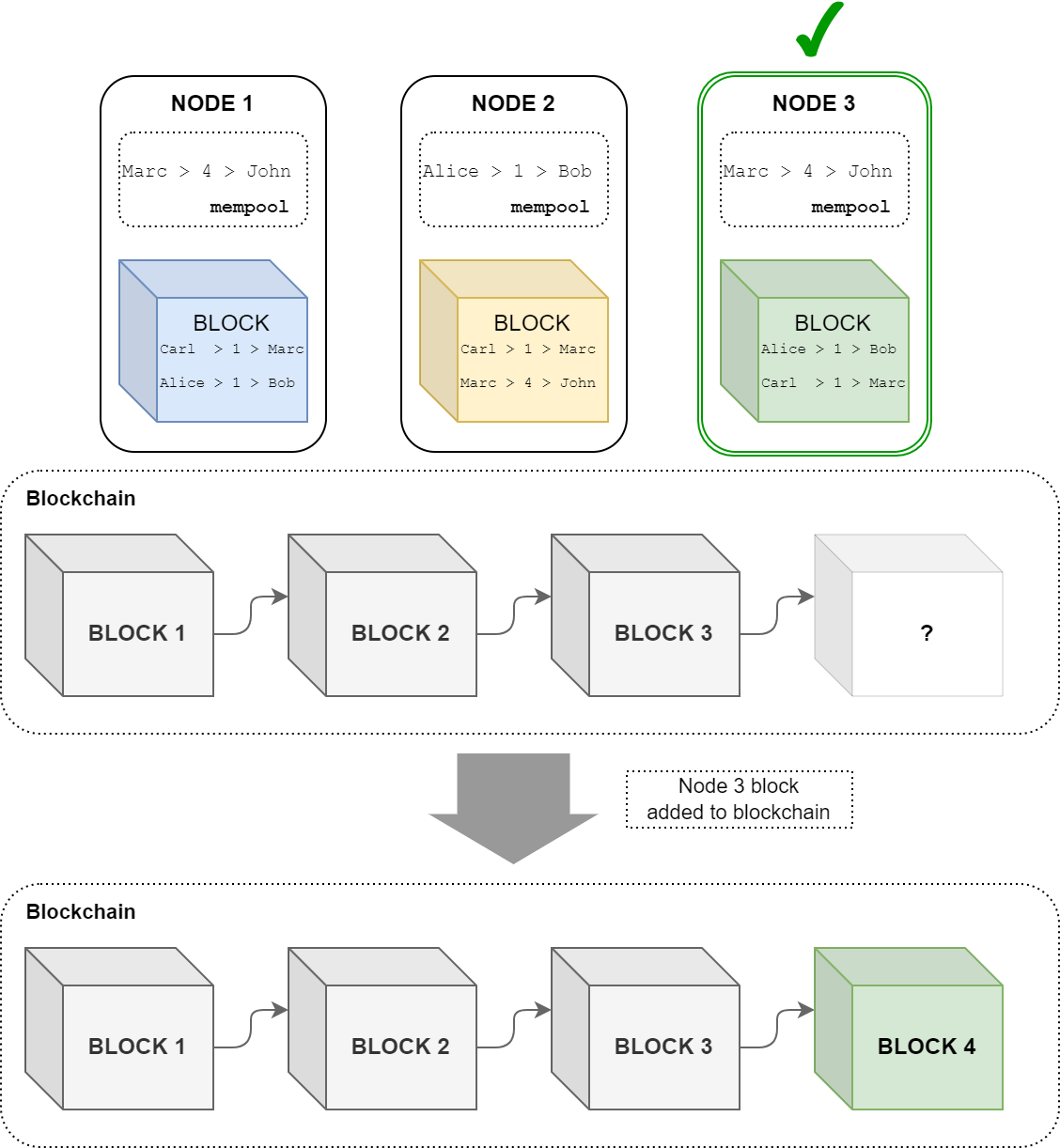

So there’s a whole bunch of transactions waiting to be validated, and that’s where the magic of the blockchain comes in. Transactions have to be validated, and all the nodes in the network will need to agree on which transactions should be validated, and the order in which they should be validated.

Each node then creates a block, the size of which is limited (and differs from one blockchain to another) by selecting pending transactions in the mempool. Once this block has been created, all the nodes compete to make its block the new reference block. The winner’s block becomes the last block in the chain. It is added to the previously validated blocks, the underlying transactions are no longer in the mempool, since they have been validated, and all nodes must therefore rebuild a new block with the transactions that have not yet been validated to try, once again, to win this competition.

Consensus

This “competition” we’re talking about is the consensus mechanism, i.e. a way of getting everyone to agree on the next block. There are many different consensus mechanisms.

The Proof of Work (PoW) is a consensus mechanism that requires each node to make a huge number of calculations to find a solution to a specific problem.

In simple terms, it’s as if you were asked to supply a string such that md5(block + string) begins with ten times the number 0. There’s really no right or wrong way to do this.

You can simply generate completely random strings, compute the md5 hash, until you find, by chance, an entry that satisfies the condition. And at some point, in a completely random fashion, someone may test :

echo -n '[bloc data]aa33bdsk' | md5sum

# Output:

000000000035d3695b3a133766f60d42

By being the first to find this solution to the problem, their block will be added to the existing blockchain, and therefore the transactions they took from the mempool will be validated.

Proof of Stake (PoS) avoids the need for all all nodes to perform calculations. Instead, each node must set aside cryptocurrencies from the blockchain (staking). Each node prepares its block, and at regular intervals, an algorithm randomly selects a node from those that have staked cryptocurrencies. The selected node’s block will be validated, and we move on to the next block. If the node does not respect the rules or tries to cheat (by modifying transactions or creating a block that is too big, for example), his stake will be confiscated. You gotta play by the rules.

There are many other consensus mechanisms, but you get the idea. The goal is for a random node to validate a block regularly, but it should not be possible for the same node to validate all blocks. Everyone is in competition.

Incentives

Rest assured, the individuals behind these nodes are not blockchain enthusiasts working for free. Every job deserves a salary, and that applies to the blockchain as well. The people who are part of the network, verifying and validating transactions, earn rewards.

To send a transaction on the network, users must also send a small amount called transaction fees (known as gas in Ethereum). Thus, when someone validates a block, they will collect the fees from the transactions they have validated. It becomes clear then that as a user, if we want to ensure that our transaction doesn’t stay indefinitely in the mempool, we need to pay sufficient transaction fees to be in the average range or even at the higher end if we want to be prioritized.

Furthermore, with each validated block, a small amount of the cryptocurrency is created from scratch and sent to the validator. This increases the total circulating supply of the coin.

Conclusion

These paragraphs hopefully clarify the overall concept of a blockchain and serve as an introduction to the next articles that focus on the Ethereum blockchain, specifically the Ethereum Virtual Machine, which enables the execution of smart contracts, and the security challenges associated with this decentralized code execution. See you soon!